These Virtual Exhibitions Draw on the Real-Life Health Benefits of Art

The exhibition “AORA V: nature/nurture” (on view through Feb. 27, 2022) takes place within four tranquil galleries that, thanks to ample room-length skylights and picture windows, are awash with natural light. A soothing soundtrack accompanies the spaces, each of which features paintings, photographs, sculpture, and other objects by emerging artists from around the globe. To get a closer look at one of the pieces, there’s no neck-craning required. Visitors simply press the “up” arrow on their keyboards: All works in the show, and the building it’s housed within, only exist online.

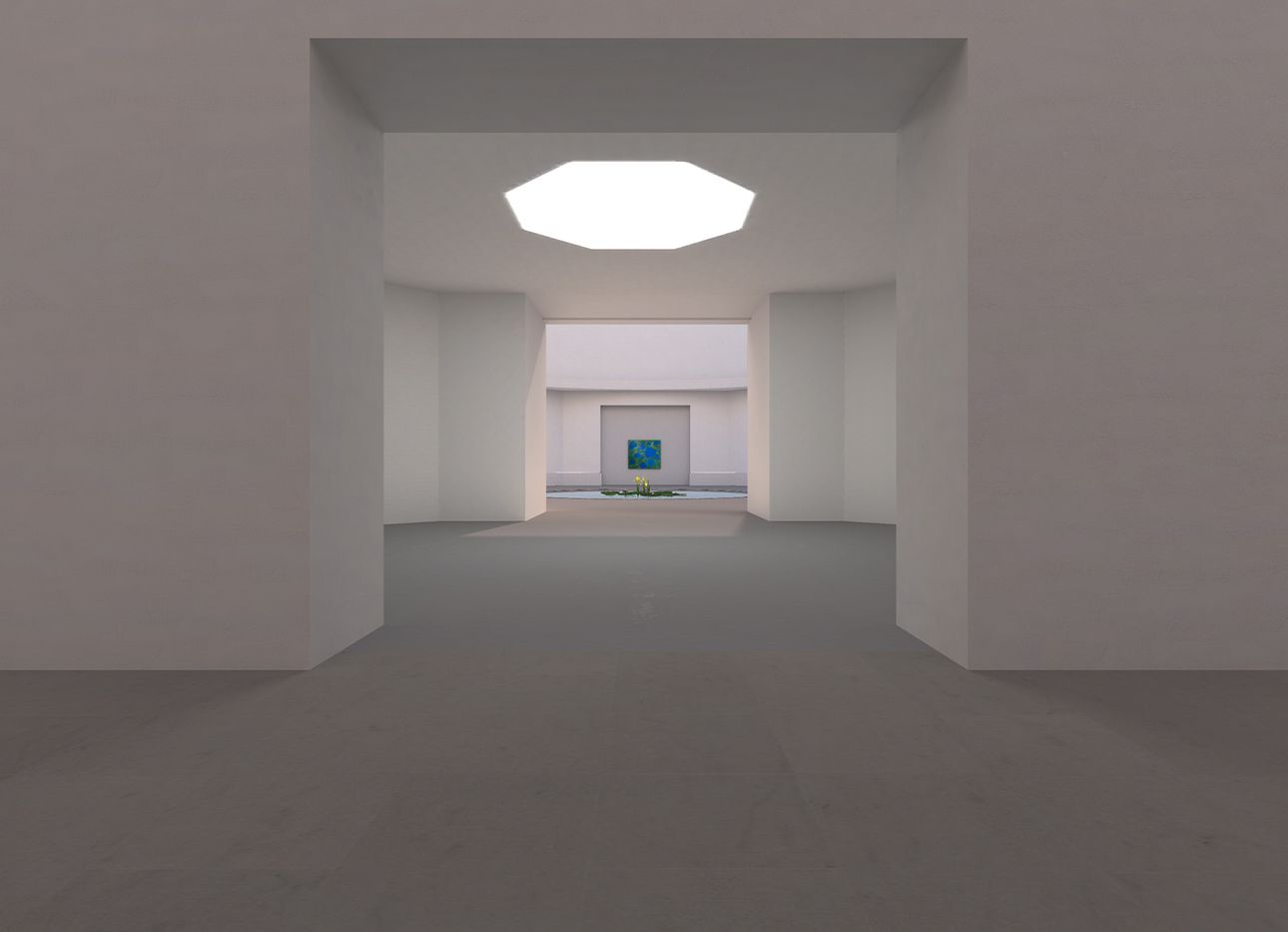

The presentation is the fifth spectacle created by AORA, a digital platform that combines art, architecture, and sound to create multisensory experiences that are available to anyone with an internet connection. Its work draws on the proven health benefits of creativity and the arts, including reducing pain, increasing relaxation, and shortening recovery periods from injury or illness. AORA’s exhibitions (or “chapters,” as it calls them), form the nucleus of its efforts, and take place in a sprawling virtual building designed by Benni Allan, the founding director of London’s EBBA Architects, who co-founded AORA with curator Jenn Ellis, in June 2020, when most galleries were closed due to the pandemic. Like a real-life viewing room, AORA’s virtual iteration serves as the backdrop for each exhibition; viewers explore the premises by using their arrow keys and clicking on the artworks and a corresponding “+” button, which reveals details about them in the format of wall text.

To date, AORA has featured artists from Papua New Guinea, South Africa, New Mexico, and beyond, and established Exchange, a series of programs—exhibition-based panel discussions, studio visits, concerts, movement classes, and more—that foster a sense of community. (Last week, AORA hosted a pop-up event in the Mayfair district of London that featured an art sale and a performance by sonic artist James Wilkie, who composed the aural arrangements for “AORA:V.”) Those wanting to engage further with the company can sign up for a membership, which unlocks access to live and in-person activities and discounts to AORA’s online shop, which includes a curated collection of tea, candles, and other calm-inducing everyday objects.

We recently asked Ellis and Allan about putting their project together, and about the ways in which virtual exhibitions can democratize the art world, increase accessibility, and engage the senses.

How did the idea for AORA come about?

Ellis: Five years ago I was in a hospital, and I noticed that there was art on the walls. I started wondering why hospitals would bother putting it there, which sent me down a rabbit hole looking into the neurological benefits of art—specifically, how it’s been proven to alleviate pain, reduce stress, and improve mood. Based on this research, and drawing on my background as a curator, I began to contemplate the ways that I could help bring these benefits to people who are immobile or [otherwise unable to visit museums in person].

I built and tested the first prototype [in 2017], and it was really awful. What it was precisely not doing was activating the senses. I realized it was because I’d tried to mimic reality, replicating a white box in a virtual space.

Then you asked your friend Benni to help you create a better version of the virtual gallery you were envisioning. When designing it, what aspects of the in-person art-viewing experience did you want to replicate, and which aspects of it did you leave behind?

Ellis: We thought about spaces and places that inspire us—ones where art, architecture, and environment come together—like Dia Beacon in New York, Naoshima in Japan, and Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the U.K. When you go into the chapel space at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, for example, the artwork really fits in. There’s a melody between the art and the space. At Naoshima, there’s a beautiful Monet room where you take your shoes off and walk around in your socks, and your chest just expands. It’s beauty. And it’s not beauty just at eye level; it’s in your fingers and toes. That’s the sense of harmony we wanted to achieve. Our mission was to build in the digital world with soul, and to make it for everyone.

Allan: What’s amazing about the virtual world is that you can do anything. But we weren’t interested in creating something that was too fantasy-based or that completely transports you to another world. We want to take people somewhere, but we want them to be reminded of how they sense things in the real world. There are characteristics about the galleries that feel true to how you’d experience things in real life, such as the sense of scale, the openings of doors, and lighting that mimics sunlight.

The galleries also feel surreal, though—almost dreamlike—and create a sense of calm as one toggles through them. What architectural elements did you include to facilitate that serenity?

Allan: Each of the halls is designed with a very specific purpose, and to convey a certain feeling. The main space was a combination of various inspirations, including the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, which is both a vast space and a meeting place. The entry hall has arches that are envisioned as gateways that invite the viewer to move through the space. The entire environment is meant to feel like a continuous enfilade. And at the end of the central hallway, you have an unobstructed view of the sky—it’s infinity. The rooms are designed in such a way that you can’t really rush through them. You have to take your time, experience the art, and experience the space.

Countless virtual exhibitions have taken place since the pandemic began—many of them, it seems, with the primary aim of enabling the continued sale of art. From a design and curatorial perspective, what are the benefits of creating online art-viewing experiences beyond the art market?

Allan: Prior to AORA, I‘d never done anything in the virtual space and never thought I would. I’m very much about tactility. What it has done is allowed me to completely reimagine how I operate. It’s given me a new set of tools. I’d previously done a couple of projects focused on the ways in which architecture can affect one’s mental state—one about dementia, and one designing spaces for young children—and I was able to apply a lot of that knowledge to creating AORA’s galleries, which has allowed me to learn other things that I use in my [real-life] projects. It’s a really beautiful back-and-forth. That’s one of the most rewarding things about AORA: I’m constantly having to learn. It’s pushing us and allowing us to do things we never would think about doing otherwise.

How do artists benefit from showing work in digital spaces?

Ellis: We’ve collaborated with more than one hundred and forty artists and galleries from all over the world, but not a single one has shipped an artwork. There’s something quite incredible about going to a URL link and being able to engage with artwork from India, Brazil, South Africa—you name it.

We started off showing art that existed in the real world, but then, last November, we did an open call around the theme of sculpture and the body for our third exhibition. That’s when we started exploring the possibilities of digital sculpture, which is interesting because one of artists’ primary limitations is production costs. In the virtual world, they can play a bit more. We’re at the forefront of thinking about creation in the digital space, and understanding how that can be a very real source of opportunity.