Nike Imagines the World 50 Years From Now

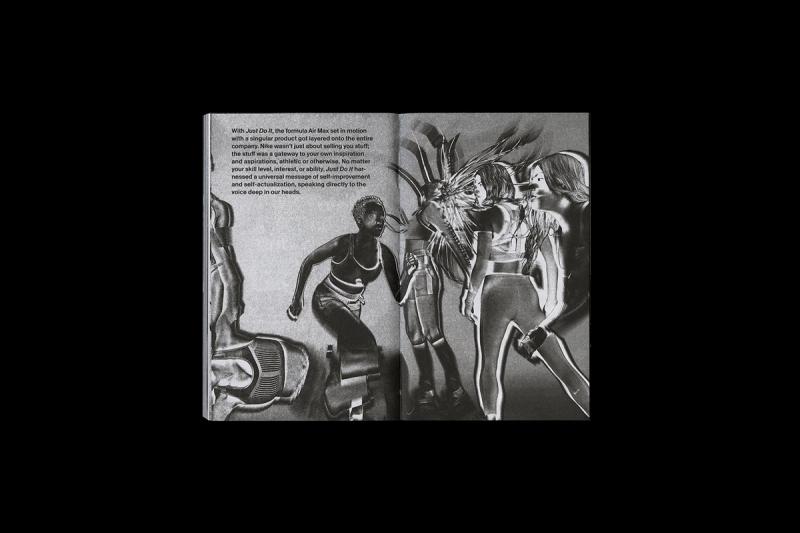

From its classic swoosh logo, to its signature Air Jordan silhouette, to its legendary “Just Do It” tagline, to its recent 50th anniversary video short by Spike Lee, Nike knows how to expertly engineer and craft its brand down to the tiniest detail, and how to subtly zoom out and in to the zeitgeist.

Yet, when it comes to books, the Beaverton, Oregon–based behemoth has never put out a true cult classic—until now. No Finish Line (Actual Source), the brainchild of Nike’s chief design officer, John Hoke (the guest on Ep. 61 of our Time Sensitive podcast), extends out of Nike’s 50th anniversary celebrations last year and puts forward a sort of Nike design manifesto for the next five decades. Featuring an introductory essay by Hoke; a series of provocative and projective texts by the writer, editor, and former Herman Miller global brand director Sam Grawe; and far-future speculative fiction by Geoff Manaugh (the guest, along with his wife and partner, Nicola Twilley, on Ep. 33 of our At a Distance podcast), this slim, red-covered paperback—an “anti–coffee table book,” Hoke calls it—is all at once evocative, generous, ambitious, literary (but unstuffy), and punk. Substantive yet easily read in a single sitting, it is an invitation to ponder time: the ancient past, the present, and the distant future—all through the lens of humanity. And, of course, of Nike.

Designed by the London firm Zak Group, the volume has a vintage vibe, in the vein of a Penguin Classic, that looks even better with a crease down its spine. (Something about its retro feel led me to think of Ridley Scott’s iconic “1984” Apple ad for the original Macintosh computer.) This is a book to throw in your bag, to take on the subway, to shove in your back pocket, to leave at the gym. Says Hoke: “We want it dogeared, we want it annotated, we want it passed on.” Unlike Nike: Better is Temporary, a recently published Phaidon title (also by Grawe) that charts Nike’s phenomenal products and path to the present, No Finish Line presents a giant, moonshot leap into the future. Also addressing certain pressing, climate-related realities, it offers a realistic yet hopeful outlook.

Here, Hoke discusses the strikingly, refreshingly avant-garde project.

Reading the book, I noticed two words in particular pop up several times: “relentless” and “harness.” I was wondering what these words mean to you. How do they describe the past, present, and future of Nike?

That’s a great observation. To begin with, I think about “relentless” as a mindset of Nike that has always existed, which is this notion that we are about the progress of sports and the progression of athletes within the landscape of sports. It takes a relentless mindset to continuously and repetitively push hard against the status quo, and the boundaries that have always existed. We have always been a company that relentlessly leans into those thoughtful constraints and says, “No, we’re gonna push against that.” I think “harnessing” is taking that relentless activity that we do at Nike, and giving it to athletes, and then seeing what unfolds.

I also appreciate how you write about the iconic Nike orange shoebox as a “portal.” I was hoping you might elaborate on that a little bit.

The idea was that the box itself is far more than just the vessel. It’s a representation. When you receive a box at Nike, and you open the lid, and you look down on these products, you’re actually looking down at fifty years. That progression of thinking is delivered in this particular box, at this particular moment, knowing that it has a connection—a lineage—back to the beginning, and it also has a projection going forward.

If I was really truthful, Spencer, what I would tell you is that it was my Don Draper moment. Did you ever watch Mad Men? [Laughs] Remember when he’s like, “This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine”? To me, it’s not a box, it’s a portal.

I’m obsessed with the notion of a portal in general. Design, at its best, is often a portal. In 2020, I published a book about memorials [In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials], and all the memorials I chose to include in it I viewed as portals. It’s interesting to hear you talk about a box in that way. It’s almost like a tribute to the past, but also a portal to the future.

As much of the nostalgia that we were talking about at Nike last year, meeting our fifty-year mark, it was as much about looking forward—as much about aiming a telescope, and then, using that metaphor, “Hey, we’re never done.” There’s a design lineage between the timeless, the timely, and the future. That became crystallized in my mind of what to do—both celebrating, looking backward, but also unleashing the future. We’re at this unique moment in time, and I was lucky enough to have been here for thirty years when Nike turned fifty last year.

We get to do both things. We get to stop and celebrate, but also, we’re back at it. We’re going into our fifty-first year. That portal is, I hope, ever-expanding.

The book also references the ancient past. Toward the beginning, there’s this image of a Paleolithic hand ax. I was wondering, how do you think about that object within the context of Nike?

Part of the human experience is that we’re one of the few mammals that’s lucky enough to be wired to understand the power of a tool—and what a tool can do in terms of advancement and progression, whether that’s an ax or an arrowhead. It’s that uniquely human act of understanding your constraint and understanding your context, and saying, “We can do better. We can make the ax sharper, we can make it lighter, we can make it—”

A better grip.

Exactly. This may seem a bit of science fiction, but it’s also deeply rooted in our humanity. Which is: We are wired for progress. We understand tools. We’re reaching this age where the tools are amazing. It’s incredible what’s coming. So how do we leverage what those tools are and stay really grounded in our humanity?

The last thing I’ll say about that, because I love that you picked up on that: That tool is specifically a physical tool. It’s in your hand. You’re chopping, or you’re creating activity. And these are tools that we’re creating [at Nike] that go on peoples’ bodies, to stay wired to their biology, to stay innately human, and yet push that possibility and that potential farther and broader than we’ve ever thought possible.

There’s this line in the book: “The key driver of design at Nike has always been data.” Which is something you talked about on your Time Sensitive episode last year. I feel like so much about designing at Nike, from what I understand, is about how you use these new, cutting-edge tools—algorithmic design, parametric modeling, machine learning, DALL-E 2, whatever. What are some of the more breakthrough examples at the moment that you can cite, that are exciting you, that the team is thinking about and interacting with and exploring?

As designers, we have to realize that data does not dream. We do. Source material is exponentially going to be a part of the future. It’s knowing how to curate that information, and being able to have an intuition beyond the empirical data, and start to extrapolate the things that we see—that a human might see—that perhaps an A.I. might not see. I find that to be, basically, the grounds of the future of what design is. The value chain between an idea and output is shrinking rapidly with the greater use of things like DALL-E 2 and other A.I.

In the book, A.I. is described as a tool to dream with.

I’ve said before, “The good news is that the future is always unwritten, and the better news is that it’s never unimagined.” DALL-E 2 is a human’s imagination on rocket fuel, basically, and my imagination never sleeps, so to have to have a partner and a co-conspirator that’s sitting right there, that I know won’t do anything until I prompt it or I intend to use it, and to see what it’s coming back with—and the breadth and pace of this—I’m still grappling with it, to be honest with you.

But I’ve also had a chance to see where it’s going. What happens is, designers become more about curating and adjusting parameters, and still editing and beautifying. I’m incredibly excited. It’s such an advancement for our company, because it takes the data and puts it in its rightful place, and then empowers designers to make the choices that designers make, but far faster and with much more fidelity.

Another interesting angle of the book is that it’s also asking in a genuine way, How do we acknowledge and address the climate crisis? Obviously, it cites the Space Hippie as one example in this area. But there’s also Nike’s commitment to net zero emissions; there’s Nike’s thirty percent drawdown by 2030 of greenhouse gas emissions. Fifty years from now, whether it’s through recycling, upcycling, biomaterials, mushroom leather, whatever, where do you see the bulk of Nike’s materials coming from?

Just speaking off the cuff and really speculatively, I would presume that virgin material would be something that is never used. That we would have unlocked the ability to reimagine matter, over and over again. Nike would be a leader in the economic ecology of constant reimagination of matter. I’ve said it before: “Making matter matter more because it’s reimagined all the time.” That lets us serve citizen athletes and citizen consumers as citizen designers.

This is maybe a poetic way of thinking about it: Everything that we do as designers is to be reclaimed and reimagined. There would be very, very few “heirloom”-type pieces that would stay with people for emotional connections and reasons. You would be engaging in a service economy and exchanging materials back and forth. We, as humans, would begin to replicate some of the power of nature.

My hope would be that, if we’re here in fifty years, we would have cracked that code, and we would have taken a leadership position that we were proud of. That there was no compromise. That there was a full-throated agreement that we need to change what we’re doing. And that change can be super productive: to continue sports, to make the planet more livable, and to drive the expressions of design in ways that I couldn’t describe right now.

This book largely gets away from corporate-speak and leans into: How do you talk about a major, global company such as Nike in a way that’s actually intimate and human and not ignoring the extreme realities facing our planet right now and in the future? Very often climate issues get brushed under the rug by major corporations, but here they’re explored in a way that’s projective, forward-looking—

And hopefully, if I can add to your thought with optimism, [they’re explored] in a way that also shows that Nike was not powerless in this fait accompli. That we were action-oriented, and we called [the climate crisis] what it was, and we decided to make further investments as a company, both in innovation and design, to meaningfully make change.

We started this book project years ago, and I think one of the coolest things we decided was that, while many companies would put out this giant, glossy coffee table book that was meant to be viewed, we said, “No, this is an anti–coffee table book. This book is meant to be read and reread, and consumed as an optimistic speculation on the future.” Because we still want to sit and go, “That was cool, but the future is unwritten. And we’re gonna go figure it out.”

I love that you bring up this almost-literary factor to it, because one of the things that stood out to me as I was finishing it was the reference to Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s 1933 essay In Praise of Shadows. Of course, that has become such a cult text. I can imagine No Finish Line will one day become its own sort of cult text, too.

A part of it is also my own fascination with the role of science fiction. At its best, it becomes a predictive course of, “Oh, this, this can happen!” It also puts several questions in front of you—questions of utility and beauty, and the role of society in the future, and now more than ever the role of technology. What the book is striving to anchor back on is that, wherever we go, [Nike is] going to be this biological piece that is going to be there.

In Praise of Shadows is ninety years old this year, so it’s fun to imagine No Finish Line ninety years from now. There are so many timeless lessons in In Praise of Shadows—and obviously, certain things in it that haven’t aged so well—but I think it’s interesting when you think about how a text endures, and how certain ideas remain core and essential.

It becomes referential. When you read it, it’s there with you. Whether it’s in the conscious or the subconscious, it’s there. It becomes a part of the journey.

That and many other books and films have always been references to me, whether that’s Metropolis or Blade Runner or Star Wars. They’re in our collective subconscious. They become central to the narrative of where the future is going to be. That, to me, is an exciting part of the book as well: the acceptance of the unknowing, where this all goes, because who could predict a pandemic three, four, five years ago? And who’s going to be able to predict the disruptions that will inevitably be in front of us? I hope that this is a treatise about resilience and humanity. The relentlessness and the uptake of that—the harnessing of that—is super important. For our company, anyway.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.