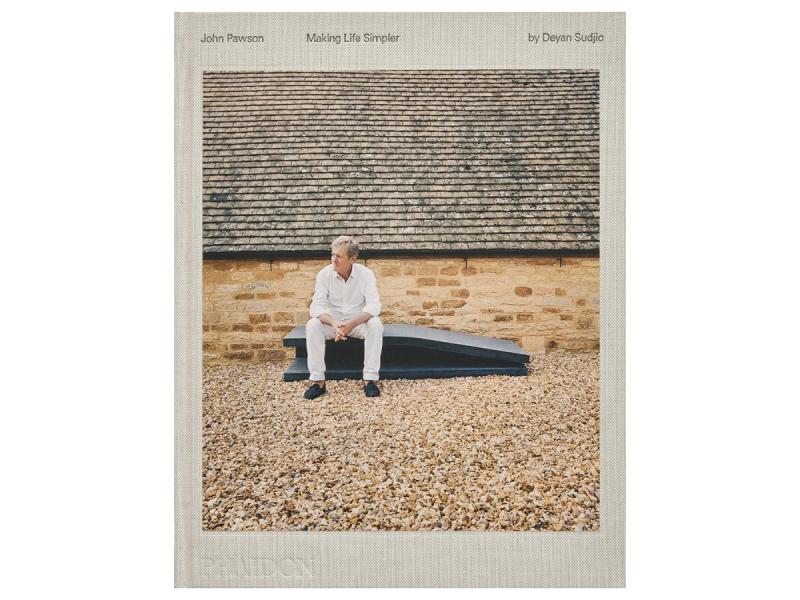

John Pawson’s Approach to Making Life Simpler

Across his 40-year career, the British architect John Pawson has realized a vast portfolio of impeccably refined projects both large and small, whether a yacht, a Los Angeles hotel, or a door handle. Essential to his practice has been the production of books, including, in the case of his latest title, Making Life Simpler (Phaidon), one by his longtime friend the design writer and critic Deyan Sudjic, a book not only about his work and visionary eye, but also his life as a whole.

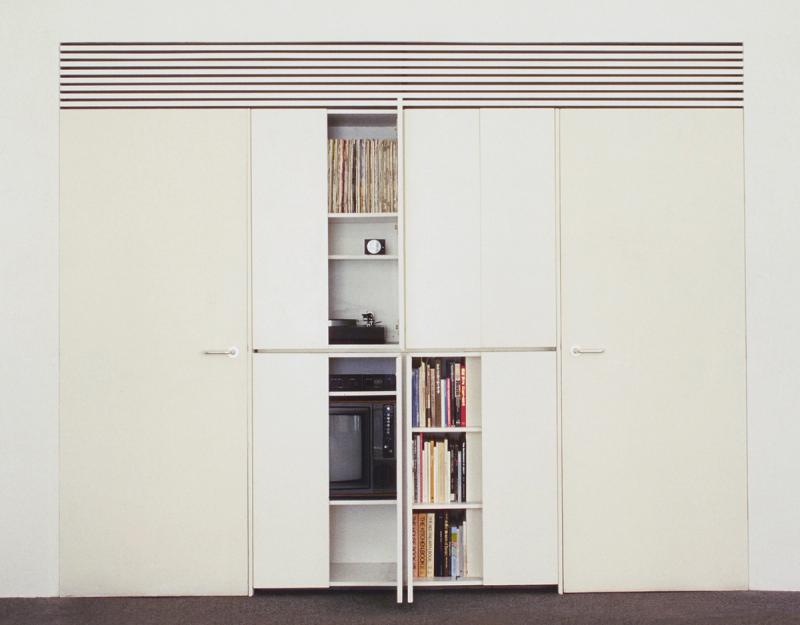

Though he’s renowned for his serene, minimalist structures—from the Calvin Klein flagship store in New York (1995), to an abbey for Cistercian monks in the Czech Republic (2004), to the Jaffa Hotel in Israel (2018)—Pawson is also a master in making serene, minimalist books. Beginning with his first, the aptly titled Minimum, in 1996, he has since published 11 more, including Barn (1999), about his restoration and renovation of a derelict 18th-century Dutch barn in the English countryside; Architecture of Truth (2001), a reissue of photographer and artist Lucien Hervé’s pictures of the 12th-century Cistercian Abbey of Le Thoronet in Provence; and A Visual Inventory (2012), featuring a curated collection of 288 snapshots by Pawson, selected from more than 250,000 he’d taken on his digital cameras by that time.

Here, Pawson discusses his affinity for bookmaking; his long, slow, peripatetic path to becoming an architect; a recent visit from Kanye West to his country house in the Cotswolds; and the life-changing impact Calvin Klein has had on his life and career.

Let’s start with your relationship to Deyan, whom you met for the first time in 1984, when he was the editor of Blueprint magazine. Later, in 2002, Deyan invited you to create a Venice Architecture Biennale installation, and of course, you went on to create the London Design Museum, where he was the director at the time. That museum is your ultimate collaboration with Deyan. Tell me about this forty-year friendship.

It’s been amazing. He’s seen every peak and trough in my life and career, both in my personal life and my professional life. He was there when I first met Calvin [Klein], physically, for the first time.

He was in the room with you two?

When I met Calvin, he said to me, “Can I see something you’ve designed?” The only thing that I could find was my own house under construction, and then Hester Van Royan’s apartment. When we went round there, Deyan was there interviewing Hester. There’ve been all these instances. We were in East Hampton when all the fuss with Martha Stewart happened—the fight with the neighbor [Harry Macklowe].

But I first met Deyan because I wrote to him, right at the very beginning, when I just finished Waddington Galleries [now Waddington Custot], and I invited him to see it. I’d never met him before. We walked around the gallery, and of course, I was so proud and pleased with it. But for a publisher or a critic, there’s nothing in the gallery to show apart from the art, and if there’s no art in it, there’s even less. There were just white walls and a floor, and a bit of light coming in. But he was very polite and diffident. He didn’t say, “Bollocks!” Later on, he found something to publish.

What was the approach to putting this book together? I think it’s interesting to think about how you transformed your forty-year friendship, which also includes so many interviews, so many conversations you’ve had together, into book form. And to do that in a way that captures your rich body of work.

He’s a good editor, for a start. It’s interesting what gets into the book and what doesn’t. It’s an illustrated book, so when he did it, I said to him, “Is this all?” Only fifty thousand words. I was counting the words. I was like, “This is about me. Can you not put some more words in?” Anyway, he stretched it to sixty thousand. But there’s so much you can’t put in, obviously.

I think it’s well-judged. I mean, he keeps saying to me, “Why didn’t you tell me that anecdote before? I could have put it in the book.” Actually, after the book had been written, Kanye, or Ye, coming to stay [at my family’s home in Oxfordshire] was not an anecdote for the book. Probably not an anecdote for any book, but….

Ye comes to the Cotswolds.

Yeah. [Laughter]

Well, I appreciate the nuance of the book—the kind only someone like Deyan, who knows you so well, could get. I should say this book is not simply hagiography; this isn’t, “Look at John on a pedestal!” Although perhaps, yes, the nature of this kind of book does do that a little bit. But I think what’s special is that Deyan captures a particular sensibility and spirit. I love how, early on in the book, he makes this distinction that you’re as fascinated about what happens inside your buildings as the buildings themselves. To me, that’s the kind of thing one can only come to when they look really deeply at what you do.

Yeah, I think so. The book came about because he proposed it to Phaidon—and to me, of course. Because we’re so close, I said yes. Obviously, if you think about it, it’s quite early [in my career] to have a biography. It’s obviously not complete, because my life isn’t complete. But I did learn early on with Phaidon, with my first book with them, I was saying, I want it to be this, and I want it to be that, and they said, “Well, hold on a minute. We are the publisher.”

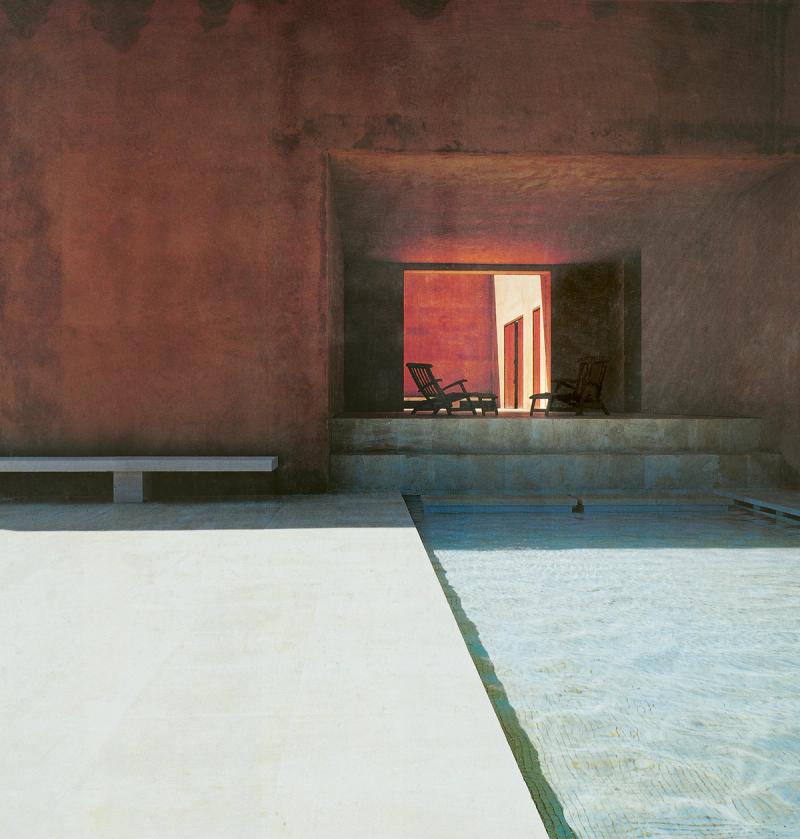

I know something about that. [Laughs] Of your work, I wanted to first bring up Neuendorf House, which was such a catalytic project in so many ways, fraught as it was with the Claudio Silvestrin situation. [Editor’s note: Pawson and Silvestrin were partners in a firm they founded together, but split up during the construction of the Neuendorf project.] But then came your book Minimum. Neuendorf, Calvin Klein, and Minimum were these tentpoles that happened early in your career. It’s interesting that a book, in that sense, is actually almost on the same plane as a building. Your books have become these sort of totemic things—particularly Minimum.

Talking about sales and things like that very early on, Phaidon explained that one thousand [sales] is a bestseller. Like everyone else, you think of J.K. Rowling or something—you think of millions being the norm. But Phaidon had the idea to make Minimum as a “mini” Minimum. They just did it. They said, “We’re doing this.” I was a bit surprised, because it was important to me, the size of the photographs and the quality of…. Of course, it went on to sell over a hundred thousand copies. So whatever criticism I had, I kept quiet.

My other books haven’t sold quite the same. The only thing that’s still in print is this one and the cookbook [Home Farm Cooking]. They reprinted the cookbook.

Not to be confused with your first cookbook, which came out in the nineties. Which I have. It’s incredible.

Oh, well, in New York, that became a bit of a cult thing recently.

Yeah, I saw The New Yorker wrote a piece about it.

Yeah, what she [New Yorker staff writer Helen Rosner] wrote was great. I don’t know her. But it’s so nice to have a young cook interested [in the book]. Yeah, that was an episode. [Laughs]

I’ve become a fairly close student of your work, and you and I have had several conversations and interviews over the past decade, yet there’s so much that was new to me in Deyan’s book. I especially enjoyed learning about the Gordon Bunshaft house in the Hamptons, which Martha Stewart purchased and then hired you to renovate and expand.

You didn’t know about that?

No! And how that project had so much promise, and turned into such a disaster.

The great thing about the human mind is that you forget. You park the not so successful episodes or the depressing episodes behind you.

It was such a special site, and such a special view. To have that pavilion of Bunshaft’s, and to be able to do a hidden extension around the back! But then you’re next door to Harry Macklowe. The irony is—I didn’t personally obviously meet him at the time, and he slightly overreacted to Martha Stewart coming next door to be his neighbor—but I ended up designing a yacht for him. I thought, I’m never ever going to meet this man. He’s so tough. Then we end up doing the yacht, [I end up] meeting his [now ex-]wife [Linda Macklowe], and visiting that amazing apartment [in Manhattan] with all the art that rivaled MoMA. It was like walking around MoMA on your own while having tea and cakes. Now all that’s gone up in steam, or air. It’s sad. How can you get divorced after all that time? “Nowt so queer as folk,” as my father used to say.

I did know the story about your connection to Calvin Klein. We’d spoken about that, how Ian Schrager passed him a small book featuring several of your projects, how Calvin literally came to London and called you at your studio. You thought someone was playing a practical joke on you, but no, it was indeed Calvin.

Yeah, that’s all true.

From there, he hired you to design his Madison Avenue showroom. But what I didn’t realize was how pivotal this commission was in the aftermath of your parting ways with Claudio Silvestrin, and how it shored up your firm financially, and also, eventually, once it was open, lent this halo-like glow to your work.

It’s no exaggeration to say I owe Calvin everything. I would even say I owe him my life, in a certain sense. Because it was so important to my career, but it also changed my life. Yes, I’d met [my wife] Catherine, I’d had children, which is really important, obviously. But just the way we’ve lived and the way things have happened have been because of Calvin.

I don’t think most followers of your work realize how by-the-seat-of-your-pants your life and career had been until you went out on your own at age 40. There’s this quote from Catherine in the book about your both meeting at a dinner party in November 1988. She says, “He told me that he was 40, had no money, and no car, and that he lived in a rented studio flat. I couldn’t believe it, but it was true.” [Laughter] I think there’s something so special about being able to capture that moment in time and think about John Pawson at 40 and John Pawson now, and wow, it does show the impact that Calvin had. But as you read along, it also shows the impact that Catherine has had.

Absolutely. She changed everything. She showed me that you didn’t have to lose money: One or two small steps, and the minus becomes a plus. Also, she allowed me to get on with it. I was able to leave the house in the morning, come back in the evening, and everything else was taken care of. But I’d also been very lucky with Hester [van Royen, my previous partner] the ten years before.

Let’s stay on the Calvin Klein commission for a moment. The store had this twenty-five-year staying power—until, of course, Raf Simons and Sterling Ruby intervened a few years ago. [Laughter] What do you make of that staying power, the fact that this piece of architecture could, in an ephemeral industry like fashion retail, become so long-lasting?

I try very hard with the work, generally, to make it ageless, or to make it as direct and as straightforward as possible so that it should stand some kind of test of time. Being realistic, you will always be able to date things.

The Calvin Klein store is interesting because I was there to make it happen for Calvin. That’s very clear. That’s true of all of my clients, really, but Calvin wanted it designed as he wanted it, and I was there to help him do that. He would have liked to have been an architect, I’m sure—or would have been, if things had been different. He had very strong ideas, and they weren’t what I would have done [had I been] left to my own devices. He had the magic dust or whatever it is, so he was able to sprinkle it.

I learned so much from him, on every level. Everything Calvin touched, whether it was the flower arrangement or the staff clothes, it was all done on absolutely the highest level. That huge backing was amazing. Working on more modest things, I realized what support I got from Calvin.

An interesting connection between Calvin and you, just going back and looking at your own family history, is textiles. You have your roots in Yorkshire’s textile industries; your grandparents had built businesses based on textiles or clothing there, and you even, for a time, worked in the family business. What was this like as a training ground for you, being surrounded by textiles?

It was huge. Because it’s all about material. Obviously, it’s about cut and design, but you start with the material and what you’re going to do with it.

It gave me an extraordinary grounding. My father used to go like this, when I was wearing something, and say, “Oh, that’s eighty percent wool and twenty percent silk.” And, “That’s in twenty-four hours” or “That’s in eighteen hours.” He knew the weight and the composition. Also, when he went to the factory, he could hear how efficient they were. He’d say, “Oh, the factory is running at a sixty-percent rating at the moment.” He could walk through the different departments and tell productivity and efficiency, just from the sound.

Then there was your time in Japan, where—again, something I didn’t know—you first arrived in late 1973, to learn and practice Zen Buddhism, but within twenty-four hours of arriving at the monastery, you found yourself, as Deyan puts it, “profoundly disillusioned.” Instead, you became an English teacher in Nagoya for three years. I wanted to hear a bit about this Japan journey.

[Laughs] You can’t believe that a 24-year-old could be so much like a daydreaming schoolboy. I’d seen this documentary about these Zen Buddhist monks practicing kendo on a mountaintop. It was filmed exquisitely. I thought, That’s me! I’m going to be doing kendo, and I’m going to reach enlightenment.

I’d lost my job with my father. My impending wedding had been canceled. All I could think of was escape. I arrived in Nagoya on Christmas Eve. Everything had failed in my life. But I was putting it into the back of my mind. This friend that I knew took me out to drown my sorrows. Then I said I wanted to go to this monastery, and he said, “Well, funnily enough, my father is a Buddhist monk. He has a local temple in Nagoya, but if you want to go to this fancy one, I can take you.” So we drove up. He said, “I’ll hang around tonight, just in case.” I said, “No, no, no, I’m here. Come back in ten years.” And oh my God, it was such a letdown.

But Japan proved fortuitous in so many ways. You got to see the temples of Kyoto and the Katsura Imperial Villa and its gardens. I’ve always wanted to ask you about Katsura in particular. Tell me about its impact on you and your thinking. Do you remember your first visit? I know you’ve been back since.

Yeah, it’s one of those ultimate buildings. But it is quite tightly controlled. You have to dig deep to go into your own world and just enjoy the very short time that you’re allowed to hang around outside or at the edge of a room. It’s like [Donald] Judd’s one hundred aluminum boxes in Marfa or the Pyramids. It’s hard to beat.

It strikes me that Katsura is also so photographic. Isamu Noguchi famously photographed Katsura. Even more famously, Yasuhiro Ishimoto photographed it. These photographs captured imaginations in the West in a way that transformed a lot of architectural thinking. Photography is such a large part of your practice, so I’m wondering, were you able to look at Katsura in that light, in a photographic way?

I think there have been other places, not necessarily photographic—I think it’s the [Ginkaku-ji] Silver Temple, where there’s one pavilion that’s the oldest tearoom in Japan, or the first one ever built, when they got the idea from China. That’s a hidden gem because you have to buy an extra ticket as part of the tour. It’s sort of a separate entity. Hordes of tourists pass it. But if you’ve got a ticket, you know you have to go off to the side alley, and then you get to this room.

At Katsura, you see the outside and you look into some rooms, but you no longer get real access. At the moon-viewing platform, you can’t go in and look out at the moon; you’ve got to look in and imagine yourself looking out. So you have to work hard.

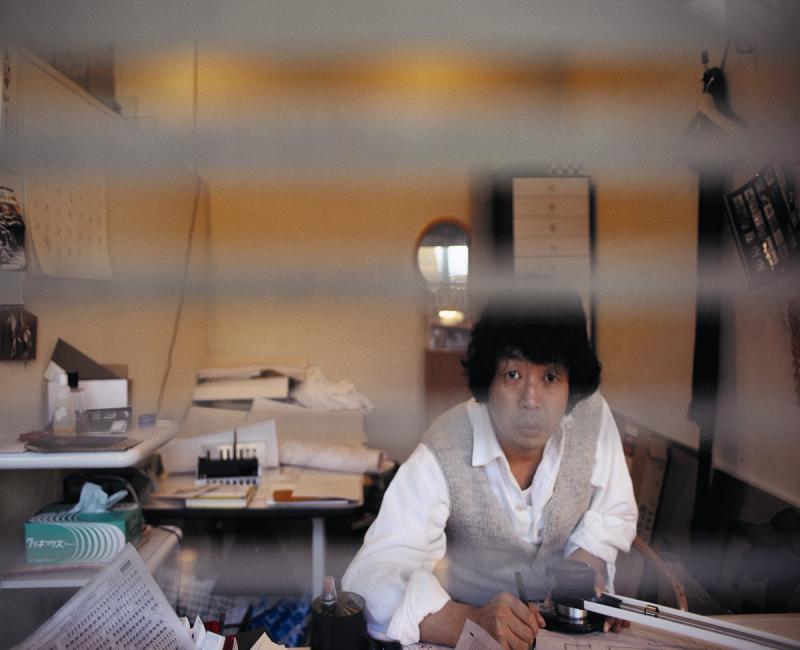

During this time in Japan, you found a monograph on Shiro Kuramata that, as Deyan points out, would change your life. Could you briefly talk about your Kuramata connection and how that paved the way toward your architectural career?

Well, I didn’t go to Japan to study architecture. I just went to Japan. It was, in a way, the first stop of getting away from my problems—or avoiding facing them. But once I was there, I started to think about the architecture. I had a lot of free time, teaching English. Of course, I had been given Domus, the Italian architectural magazine, in the late sixties, when I was working up near Newcastle. At the art school in Newcastle, they had a library of Domus. Anyway, the one that I ended up getting, from ’68 or ’69, had Kuramata’s work in it.

It had been at the back of my mind that there was a living architect who was doing work that had as much of an impression on me as Mies [van der Rohe]’s work had. I was in this bookshop, leafing through the architecture section, and came across a recent monograph of Kuramata’s work. I thought, Oh, gosh, this is everything that had been in my mind, but that I couldn’t visualize. And I don’t know how I got his number. Because I know I’d written it in the book, the copy that I’ve got. I rang up and just said, “I’m John Pawson. Can we have tea?” Just as naïvely as thinking that I could become a Zen Buddhist monk.

You formed this incredible friendship with Kuramata. I enjoyed learning that the first—and only—time you made use of a strong color in an interior was painting the cornice pink in [Hester van Royen’s] Elvaston Place apartment. Which was a tribute to Kuramata and his chromatic palette.

[Laughs] Well, actually, it’s a bit more than that. I said to Kuramata—he’d come there—“Does it look all right?” He said it was fine. I said, “Are you sure?” I went on and on. He said, “Well, you could paint the cornice pink. It’d be a little less stoic.” So I did. The pink was completely him.

I was surprised to learn how much you bounced around different disciplines early on in your career. Your path to architecture is this extraordinary journey of trial and error and, in a lot of ways, rebelliousness. Pushing against the status quo—would you categorize it as this?

I don’t think it was deliberate. It’s partly to do with having been born in Halifax and Yorkshire, and that whole Methodist [upbringing]…. The landscape, the factories, my parents’ backgrounds, the straightforwardness, never gilding anything. It was just sort of telling it as it is, or doing it as it is. Later on, with Japan, I was looking at a much more sophisticated culture and architectural things. It kind of rubbed off, but it was always there. I think everyone has several sides.

I’ve always thought of architecture as being serious, because it’s not something you can make jokes about, and it hangs around forever. So getting to architecture relatively late was probably an advantage. I tried many other disciplines, like photography, and, like my father, dressmaking. So when I found that I could actually do something with architecture, then I was really happy. Then all my energy went into that.

Throughout your forty-year career, your practice has remained at a modest scale. Even as you’ve grown it, you’ve never had more than thirty people at your firm. How do you think about this forty-year stretch, and where do you see the next—

Forty years? [Laughs] Ahhh! I have no idea, to be honest. Obviously, I’ve thought a lot about it. The last forty years weren’t really planned. I just kept my head down. But as you get to this stage, you do think about the future, for once, and succession is obviously a thing. All this work is on the back of my colleagues. It’s been very much a team thing. The idea is to hand that over. It’s not retiring, but it’s transferring, I think. Who knows? You just don’t know what happens after 70.

In a way, do you see this home you’ve made for yourself and Catherine in the Cotswolds as part of this Making Life Simpler story?

There’s some quote like, “A man who has one home is something and then a man who has two homes has no soul.” There’s some kick in the tail of that quote.

You know, the story is that Catherine wanted a small cottage that we could lock up and go to. We ended up with an estate. I would’ve bought next door. Next door came up for sale, and Catherine wouldn’t let me. She said, “We can’t even cope with this.”

So what’s next?

I’d like to build a new seaside house. Everyone else is against it, because they obviously want me to concentrate on things we’ve already got in the office—or at home.

This interview has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity.