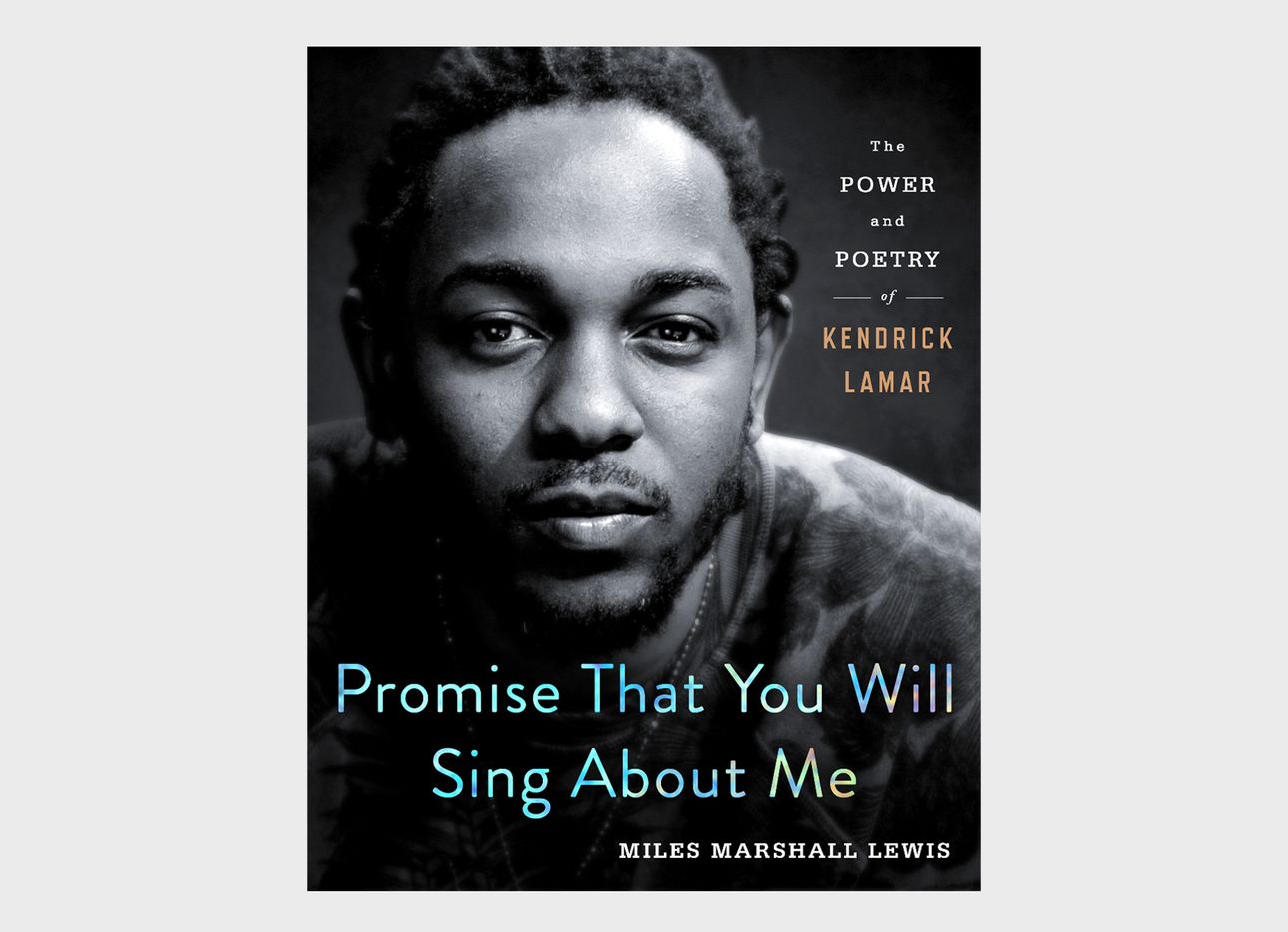

A New Book Gets to the Heart of Kendrick Lamar’s Sonic Rise

“Kendrick Lamar is my favorite rapper of the modern era,” says veteran pop-culture critic and fiction writer Miles Marshall Lewis. After Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize in music for his 2017 album, DAMN., Lewis began talking about the songwriter and record producer with his agents and editor, and eventually set about unpacking the unquestionable impact the artist has had on the music industry, and on society at large. The resulting book, Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Power and Poetry of Kendrick Lamar (St. Martin’s Press), out next month, eloquently considers and contextualizes Lamar’s work, life, and lyrics through the lens of contemporary culture. We recently spoke with Lewis about some of the sonic components that make Lamar’s music so distinct.

What drew you to Kendrick’s music, and how did you go about translating his sounds into a book?

The attention to craft in his lyrics, and the chances he takes sonically, particularly with the jazz influences on [his 2015 album] To Pimp a Butterfly, made me a major fan from the beginning. The design of Decoded, the Jay-Z autobiography and memoir, impressed me with its mix of illustrations and photographs. I felt that the way to create the most interesting book about Kendrick was to make it of the same vibe, creatively, as his albums. I also decided that some of the critical heavy lifting would be [conveyed] through side commentary by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Greg Tate, and other writers I highly respect.

How do you think about Kendrick’s songs in relation to sound?

Sonically, Kendrick’s work appeals to two sides of me: my inner boom-bap rap enthusiast, and my more avant-garde self, who loves experimental sounds. Sounwave, my favorite in-house producer at Kendrick’s label, Top Dawg Entertainment, sets down Kendrick’s vocals in a bed of melodic trap on [the song] “LOVE.,” for example, that’s more exploratory than a typical hardcore hip-hop song. Something like “Live Again”—another track I love, where Kendrick raps with ScHoolboy Q and CurT@!N$,—knocks hard like so many other rap songs before it that use the same sample of Barry White’s “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More Baby.”

Kendrick experiments with sound more than other rappers from his era. To Pimp a Butterfly proves this the most. He teamed with jazz players like Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, Flying Lotus, and Robert Glasper to make a record that sounds one hundred percent unique for hip-hop.

What else distinguishes Kendrick’s sound from other artists?

For one, he often alters the pitch of his voice, a technique inspired a little by what Prince would do in the eighties on songs like “If I Was Your Girlfriend” and “Bob George.” On Section.80, Kendrick introduces the album like a narrator by a campfire, and his voice is pitched low, like an old man’s, so he’s unrecognizable. At other times, he turns the pitch dial in the other direction, accentuating the nasal-ness in his voice.

His songs also frequently contain beat switches, which date as far back as the earliest works of Sly and the Family Stone. Mid-song, he’ll pull the rug out from under the listener by veering in a completely different direction with a new beat beneath him. Rappers like Kanye West also play with this technique, but Kendrick’s dedication to the beat switch is definitely distinct.

What do you think gives Kendrick’s work its timeless quality?

I mention in the book that a rapper trying to follow in Kendrick’s footsteps will have a lot to imitate, because Kendrick’s style contains multitudes. He’s a battle rapper who’s also politically conscious, who also appeals to female fans with love songs, et cetera. His polyglot nature applies sonically, too. His music endures because he refuses to stay stuck in one style.