Benjamin Critton on Modernist Homes in Popular Films

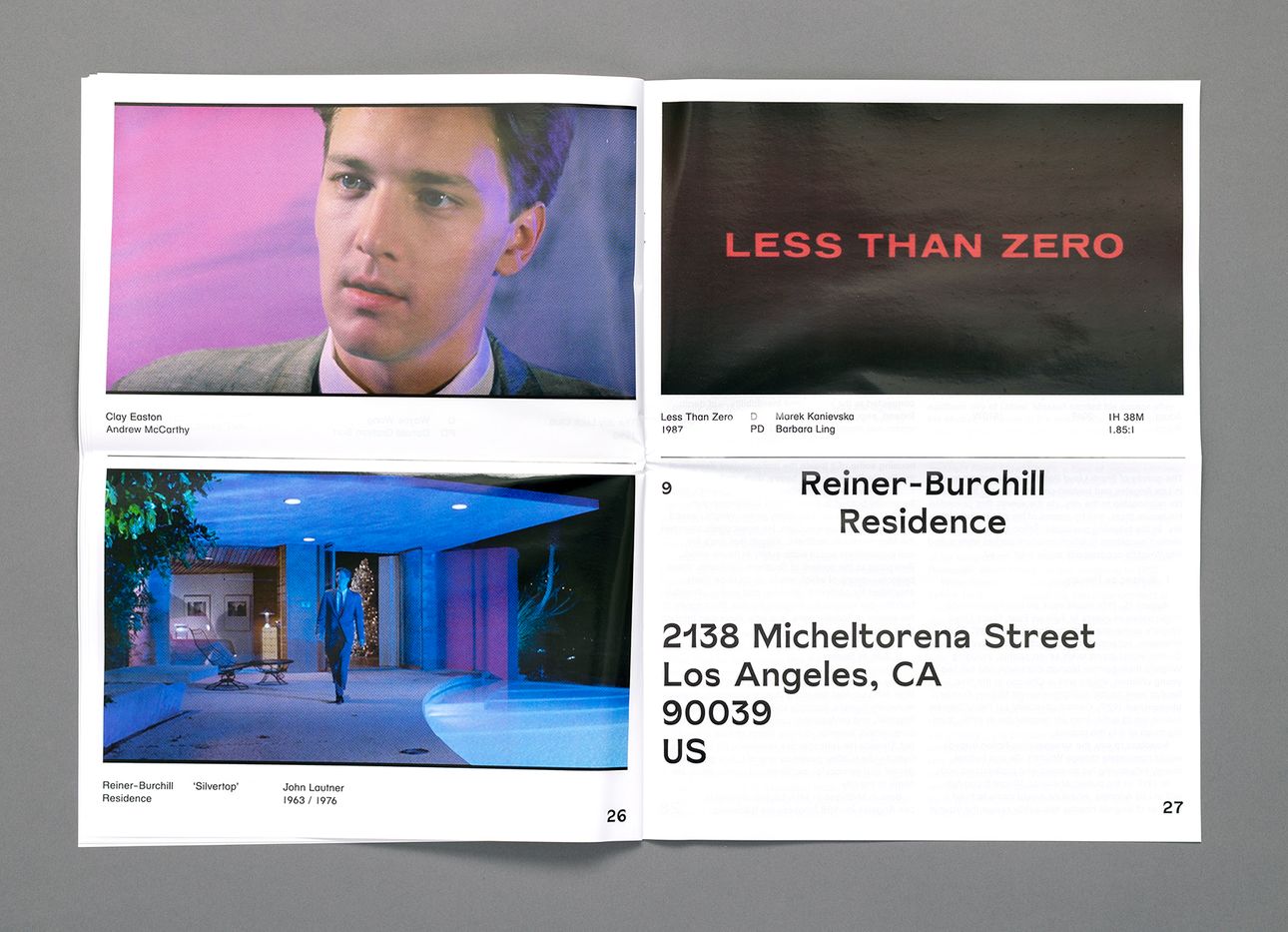

Home is where the heart is—but, on the silver screen, it can be a bit forlorn. In his recently published broadside publication Sad People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films, Los Angeles–based designer and art director Benjamin Critton explores the much-maligned trope of the Modernist home in popular culture, with contributing essays from writers Erik Benjamins, Andrew Romano, Adam Štěch, and Mimi Zeiger, that explore the topic with humor, a critical eye, and a winking irreverence. We recently caught up with Critton to chat about Sad People—the long-awaited follow-up to his 2010 edition, Evil People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films—and what filmic mood may strike him next for volume three of the ongoing project.

Between Sad People and Evil People, when did you become interested in examining the recurring trope of Modernist homes in film?

When I put together Evil People, it was before I had ever even visited or developed a relationship with Los Angeles. Toward the end of putting together Evil People, the project didn’t yet have a number. And then I had read this interview with a designer, David Bennewith, and he talks about this idea of numbering things—like, if you refer to something as “number one,” you set yourself up to do a “number two,” which keeps you accountable and culpable for making the next one. My research had led me to a lot of places, and I knew there were many instances of films that could fit into either this category, or adjacent categories. At the time, I was in grad school and had no money, so I set an arbitrary cap of ten examples in that first publication, just to sort of make it manageable at that point. Another rule I made for myself was that the houses couldn’t be movie sets, but built structures that had lives lived in them.

You’ve since moved from New York to Los Angeles. How has living in Southern California for several years now changed your reading of these spaces?

Being close to them definitely helps one understand how miscast they are, in a way. It was really interesting being in New York and on the East Coast—I grew up in Connecticut—where you’re sort of implicitly taught about the weariness of L.A., that it’s a place for movies, vice, plastic surgery, various types of crime, of seediness. It’s really twisted, and through that cultural lens it becomes really easy to understand how these homes might be cast as places and containers for that vice. The juxtaposition of a bad person in a Modernist house sort of makes sense from that gaze. In movies, they’re often played down or blown up, or made to portray the depths of bad stuff. But when you come out here, you notice how unlikely it is because you start to visit and experience these famous homes, and the effect is so calming and peaceful. They’re so beautifully and elegantly incorporated into the landscape, with a sensitivity to the climate of Southern California, that it becomes so ludicrous that it could come to be associated with some kind of villainy.

What are you watching these days? Are you feeling out any moods for a potential volume three?

I haven’t quite thought about it yet, but think I’ll do one more and maybe have it be a trio. By the time I actually do volume three it might be, like, 2030. [Laughs] But ideally it’ll be sometime next year. I haven’t even started the viewing list for volume three yet. I’m still sort of catching up, because inevitably what happens, in a really happy way, when you put something like this out into the world, is that people will come to you with all these great examples that you weren’t able to include, and you think, Oh no, that would’ve been perfect. But you can’t catch them all—that’s part of the fun in all of this.