A Photographic Compendium Highlights the Unspoken Power of Flowers

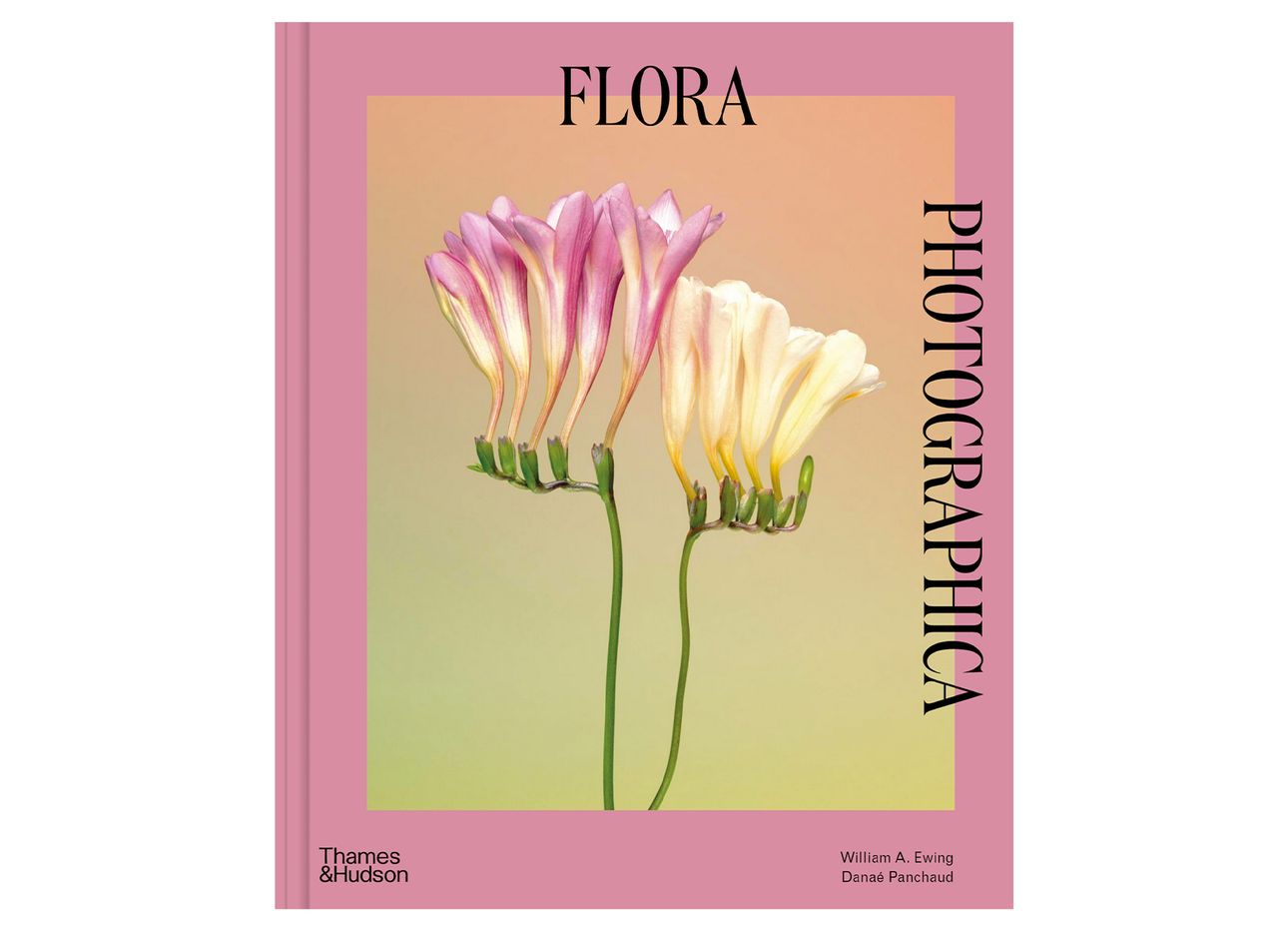

Consider the flower. What image blossoms to mind? What emotion does it elicit? For centuries, flowers have persisted as muses, motifs, and even mediums for artists seeking to capture and express some aspect of the human condition. In Flora Photographica: The Flower in Contemporary Photography (Thames & Hudson), out August 30, editors William Ewing and Danaé Panchaud compose a selection of vibrant modern floral works. The end result is a book stocked to the brim with images that dance into bloom—but there’s more than beauty beneath the surface.

To the editors and visual artists whose work populates the book, the flower is at once political, symbolic, emotional, and expressive. As an example, the editors point to the publication’s very first image: a woman raising a small arrangement of flowers. Taken amid political protests in Belarus in 2020, the photo represents a simple gesture on its own, but one bold enough, in context, to warrant arrest. The book features essays by Ewing and Panchaud, as well as nine chapters—loose categories that bind together the hundreds of photographs that fill them. From “Roots” to “Imposters” to “Fugue,” the editors channel thematic concepts that resonate across the distinct petals on page. Those categories arose organically, the editors say, after laying out the 200-or-so photos that remained after trimming down from the thousands they happened upon during their research.

Among the 135 contemporary photographers featured in the book are David LaChapelle, Valérie Belin, Viviane Sassen, Martin Schoeller, and The Slowdown’s co-founder Andrew Zuckerman. “Compiling the photographs was a very joyful process,” Panchaud says. “And it’s not necessarily because flowers tend to be colorful and nice and innocuous, but more because it was an unexpected topic for many of the photographers we were looking at. We had a lot of surprises. Of course, there are a few who are very well known—maybe twenty or thirty of them—but the rest are a mix of absolute chance encounters.”

Despite the book’s neatly organized chapters, the editors note that flowers resist static interpretation, even within a single species. The chrysanthemum, for instance, a symbol of fertility in China, represents death in Europe, according to Ewing. “What’s interesting is not so much that there is a language of flowers,” he says. “It’s that the idea falls apart when you really look at it. People want to believe that there is a language of flowers. They want to be able to buy a manual and be told exactly what the chrysanthemum means, exactly what the peony means, exactly what the rhododendron means.”

The matter becomes even more complicated as the way we view flowers evolves in the contemporary era. For Ewing and Panchaud, new trends surfaced as they put together the collection: a shift from black and white to vibrant colors, a growing anxiety over the climate crisis, a keener eye for societal issues and ills. Still, there are some traditions that have carved out a resilient foothold; despite some shifting meaning throughout history, red roses have long been gifted as symbols of romance and love.

Undisputable is that floral traditions are deeply rooted in culture. “Flowers represent something extremely profound in our species’s history,” Ewing says. “The fact that you can watch a flower live and die—sometimes within the very same day—speaks to the heart of people. This is an analogy for our own lives, a reminder of the transience of life.”