Fermentation Expert Rich Shih Explains the Particularities of Koji

Rich Shih, founder of the blog Our Cook Quest and co-author of the forthcoming book Koji Alchemy: Rediscovering the Magic of Mold-Based Fermentation, is a self-taught cook and fermentation expert who makes everything from takuan pickles to fish sauce from scratch, tweaking each ingredient, method and process along the way. Here, Shih tells us about the special fungus in koji, the source of umami in fermented ingredients like miso, soy sauce, mirin, and more.

You’ve become an expert authority on all things related to pickling and fermentation—and especially koji—despite holding down a full-time job as a mechanical engineer. How’d you fall into the culinary world?

I grew up eating my mom’s food—she’s a really great cook—and I’ve always been exposed to an array of flavors and textures. I've been super enthusiastic about food my whole life, but I think the bug for cooking and wanting to really understand more about it really hit me when I got to college, just from the standpoint of funding my own food adventures, as opposed to having to go out to eat. So I just started perusing PBS and a bunch of magazines like Cook’s Illustrated, making my way through a bunch of media research, hanging out with folks in the food industry and learning how to cook.

Maybe four or five years ago, I didn’t know all that much about fermentation, though I knew how to brew beer and make simple things like kimchi and vinegar. I would say my enthusiasm for the more in-depth stuff all started with my obsession with fish sauce and doing as many things with it as possible. I think one of the coolest things I made was fish sauce–cured bacon. I’d basically bought a bunch of fish sauce to experiment with, and at that point it only made sense to learn how to make it from scratch. Because of my engineering background—and with the rise of modernist cuisine, molecular gastronomy, and all of that, which leverages science equipment to make food—I was able to figure out these machines and processes, tinker in my kitchen at home, and help people understand them more.

How is koji made and used to create ingredients like miso?

To make koji, you basically cook the rice in a way so that it’s slightly undercooked, to create a situation so that the mold can grow well and has access to air. You’re gelatinizing the starch to make it easier for the mold to eat: If it’s not cooked enough, the mold can’t infiltrate the grain to grow. On the other side of things, you don’t want the rice too mushy or overly wet because it’ll just become this mass with no air circulation. You have to strike a balance, then you have to put an incubator that's slightly warmer than normal conditions—typically around 80 Fahrenheit/30 Celsius is a good number to hit—along with high humidity.

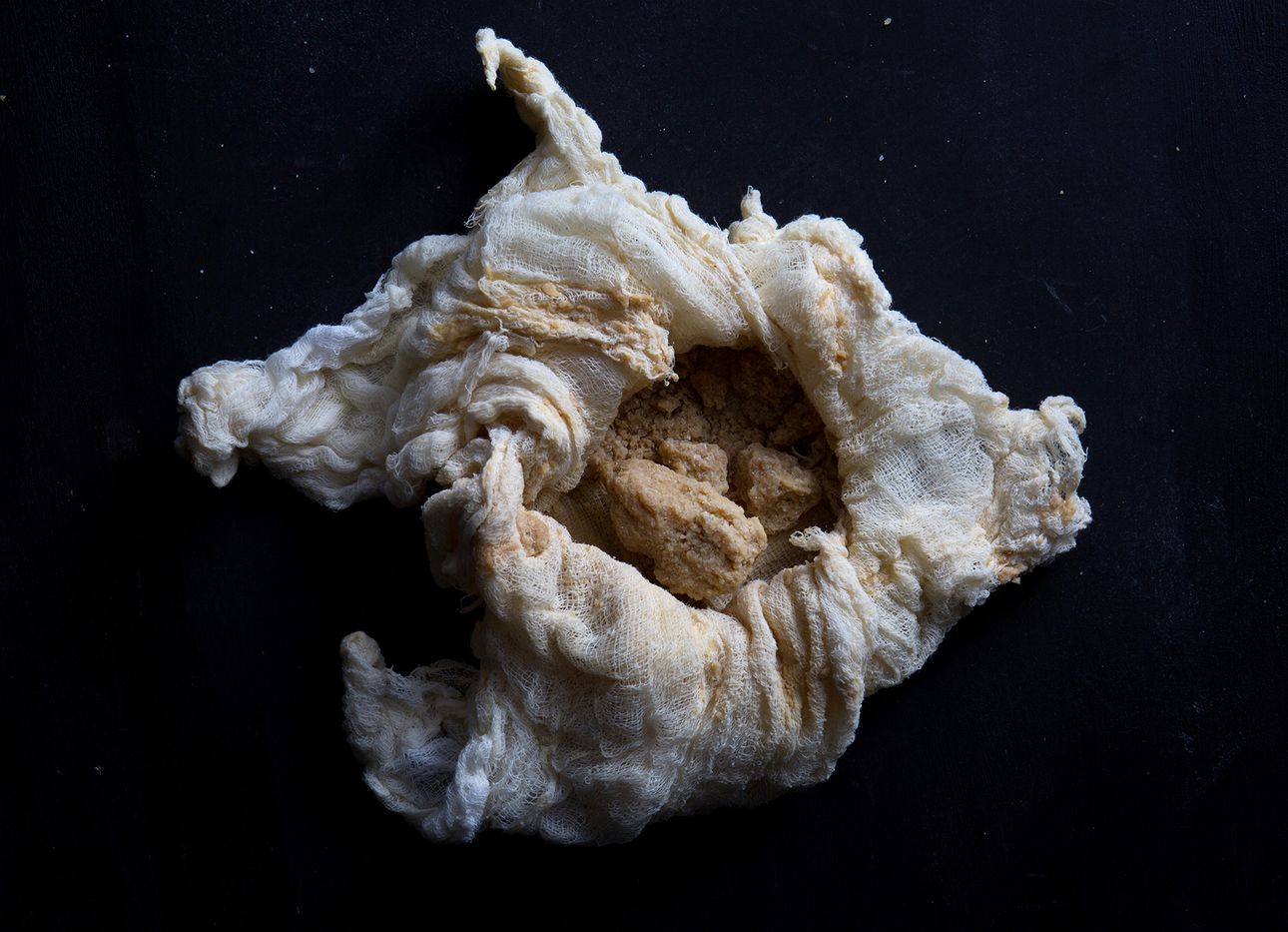

The key to growing koji is that it creates enzymes that allow you to break starches down into sugars, which feed the fermentation process. There are two sides to that: one is making alcohol, and the other side is using these enzymes to break more complex nutritional building blocks into simple ones—that makes them easier for us to digest, but also breaks proteins down into amino acids, which creates the umami in things like miso, soy sauce, and a lot of other ingredients. Basically, to make miso you take the koji starch substrate, you add a protein mash to it (that’s typically soybeans), and you add salt to it. Depending on when you prefer to enjoy your miso and what side of the flavor profile you want to drive, the rest comes down to the duration and the salt level.

What are some of the ways you’ve experimented with koji and miso?

The flavors are driven primarily by the core ingredients. So if you use rice for your koji, or if you use barley, that variation lends to a really different flavor profile. Then if you’re using soybeans as the base for your miso, which is the traditional way, or if you choose to swap it out with something like chickpeas, or some other bean or nut, those will yield a completely different range of flavors. One of the things that I kind of messed around with in the beginning was just swapping out soybeans for another type of protein altogether. For one miso variant, I used a fresh cheese on the side of ricotta, which after a couple of months had aged cheese flavors on the order of some combination of a parmesan, romano, or blue cheese. It all comes down to just understanding the basic components, what they are, and how they function, then doing whatever it is that you want by playing with those variables.