The Obscure Familiarity of Eric Oglander’s Found-Object Sculptures

Artist Eric Oglander gravitates toward materials that collapse time and space, and holds an unwavering faith in the power of found objects. The Tennessee native is something of an archeologist, with an eye for design—a hunter-gatherer who assembles his sculptures from a trove of discarded treasures, which he first started accumulating during walks in the woods as a kid. So it comes as no surprise that Oglander, now based in New York, is also a collector of folk art and antiques (he sells them via tihngs.com, and plans to open a brick-and-mortar shop of the same name in the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens later this year). It’s an interest he shares with Patrick Parrish, a fellow dealer and owner of his eponymous Manhattan gallery, where Oglander’s new solo show, “P.E.,” is on view through May 15.

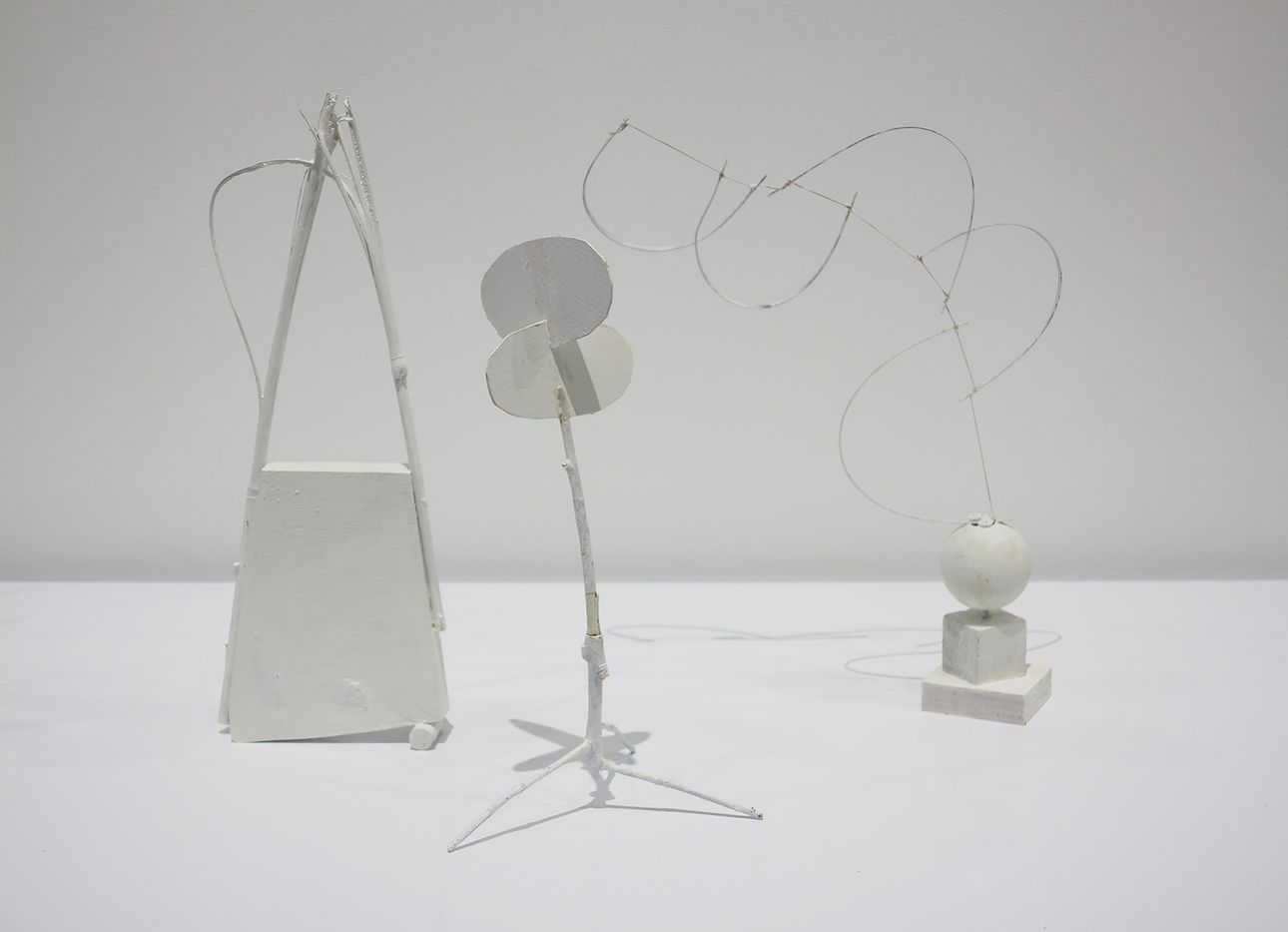

The works featured—chairs, catapults, trebuchets, and other contraptions—are presented as aesthetic assemblages of intrigue, remade readymades that are obscure yet familiar. “One of my favorite aspects of dealing in antiques is that some of the objects I find are a total mystery—I don’t know who made them or why,” Oglander says, noting that the practice shapes his art in unexpected ways. “This is a bit morbid, but when I’m making my work, I’m often thinking about the fact that I’m going to die one day. These pieces might end up in an estate sale or a flea market, where people are trying to figure out what they are.” That freedom from defining a work’s function, and a tendency toward happenstance, informs the show’s title (“P.E.” stands for “potential energy”) as much as the sculptures themselves. Nearly every piece, Oglander says, was created out of an open, unspoken dialogue between object and hand: “I tried to let the materials inform me, rather than me inform the materials.”