A New “Cultural Biography” on Karl Lagerfeld Illuminates the Person Behind the Image

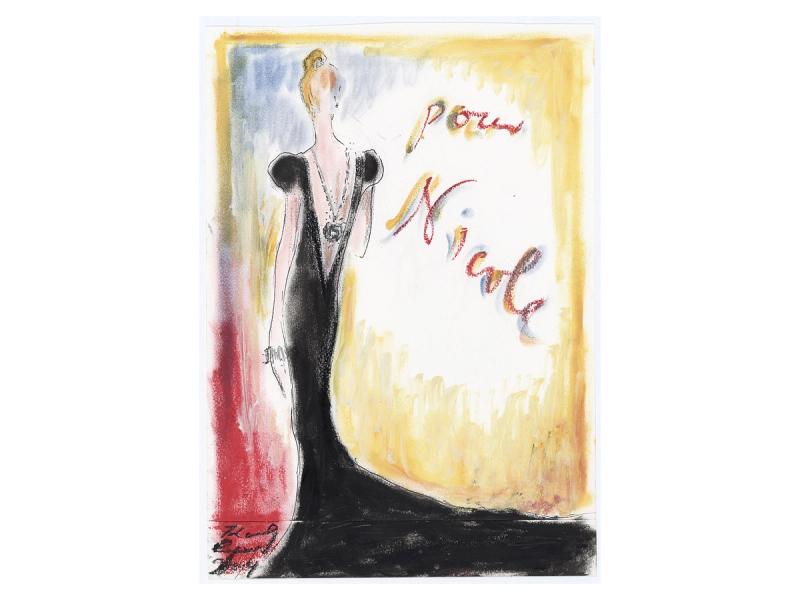

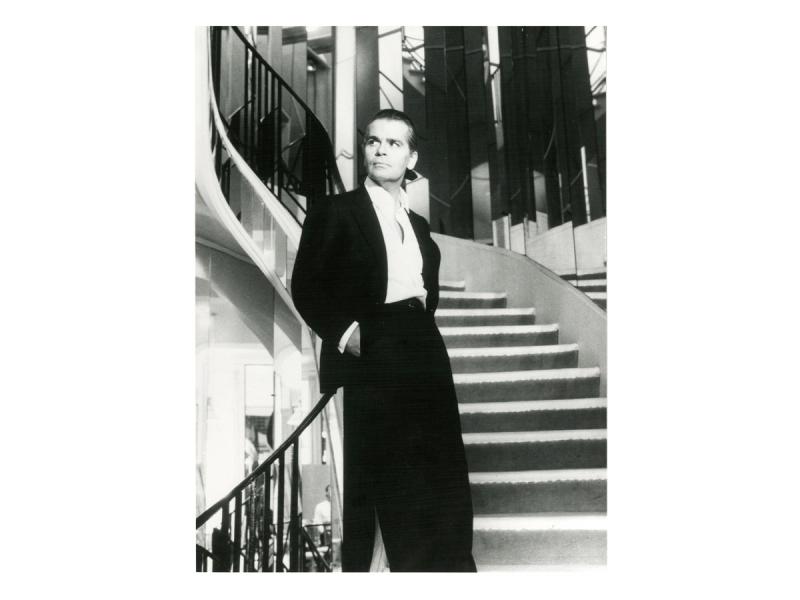

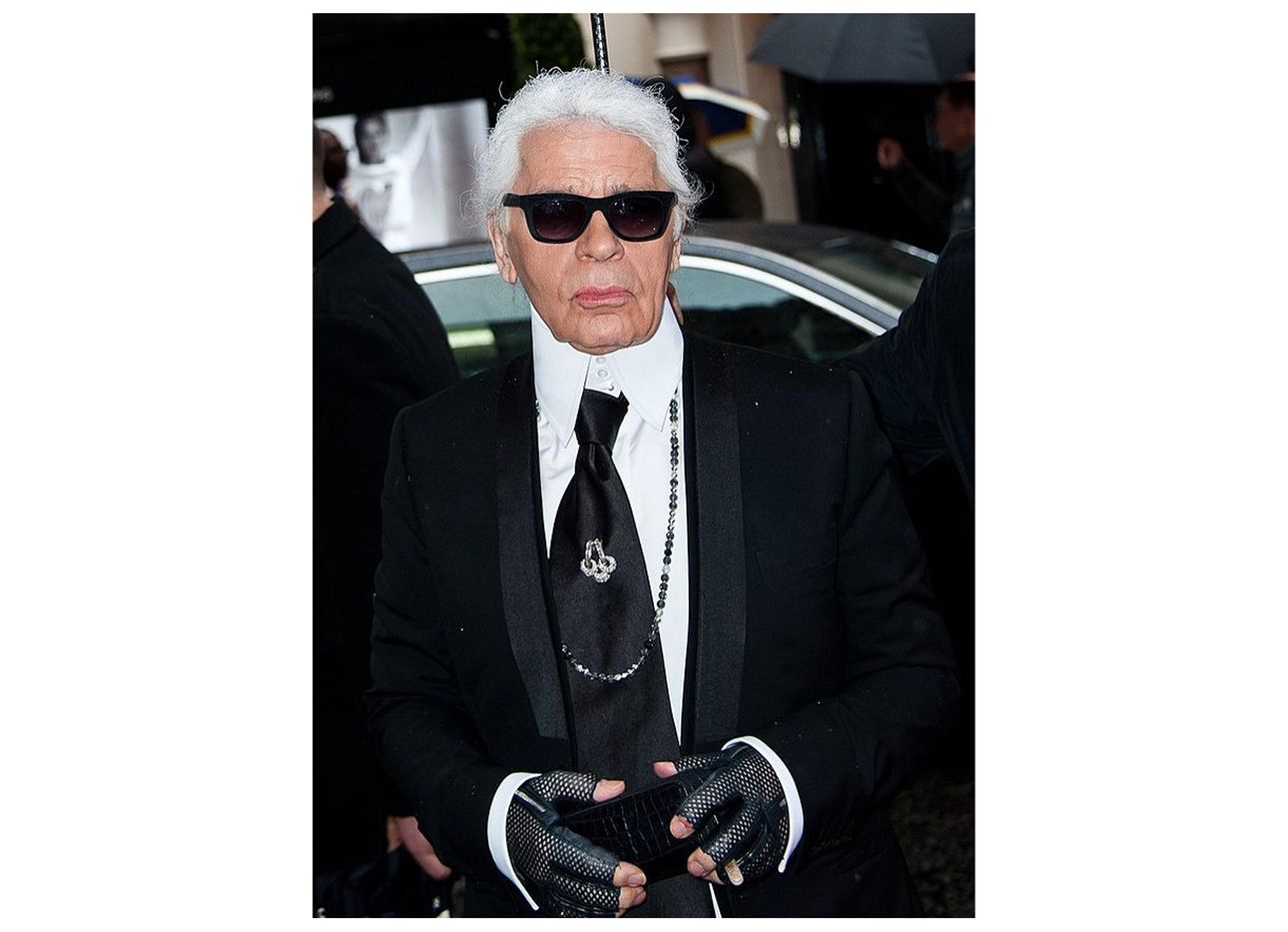

Few people in history have managed to maintain an image as precise and immutable as that of the late fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld. Invariably uniformed in jet-black sunglasses and high-collared white shirts, his hair always neatly pulled back and powdered white à la eighteenth century French bourgeoisie, Lagerfeld made of himself something of a walking portrait, over time reaching icon status. His nearly seven decade–long career was nothing short of revolutionary, from creating brand-defining collections for houses including Fendi and Chloé; to launching his eponymous Karl Lagerfeld label in 1984; to helming Chanel as creative director from 1983 until his death in early 2019—a period during which he wholly revitalized the legendary French house, propelling it into modernity.

Prolific and ubiquitous as he was, Lagerfeld’s uncompromising appearance lended him a mystique that few were able to permeate. By the end of his life, much of the world may have known who he was, but few ever truly knew him. In Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld (Harper Books), a new biography on the designer, out next week, the journalist William Middleton, who befriended Lagerfeld during his time as Paris bureau chief of the fashion magazines W and Women’s Wear Daily, sheds light on the person behind that facade. Beginning with Lagerfeld’s long-concealed childhood in Nazi Germany and continuing through his first years in Paris as an adolescent and on to his rise to international celebrity during his tenure at Chanel, Middleton presents an unprecedented panorama of the designer’s life and work. Along the way, via dozens of interviews with people ranging from Lagerfeld’s chauffeur and butler to the more elusive figures in his life—Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, author and social commentator Fran Lebowitz, film director Sofia Coppola, and actress Tilda Swinton among them—Lagerfeld’s values, aspirations, and even fears come into view. (The book’s release is fortuitously timed: This year’s Costume Institute exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, opening in May, will honor his legacy with the theme “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty.” Following Alexander McQueen in 2011 and Rei Kawakubo, founder of Comme des Garçons, in 2017, Lagerfeld is only the third designer to become the focus of the annual thematic presentation.)

Here, Middleton discusses his concept of the book as a “cultural biography,” his personal relationship with Lagerfeld, and the mark the designer has left on the fashion world and on culture at large.

What was your overarching mission for the book? How did you want to portray Karl, his life, and his work?

From the beginning, I was thinking about this book as a “cultural biography.” I knew Karl starting in 1995, here in Paris, and I was always so struck by how completely connected he was with the culture of his time. He knew everything about everything that was going on, in art and architecture and design and music. So the idea was to write a book that tells the story of his life, that’s biographical, but that really has an emphasis on his intellectual and cultural development.

A big point you emphasize at the beginning of the book is the influence that the French eighteenth century and historical figures like the German diplomat Harry Kessler had on him. I appreciated that you set the stage with his adolescent influences, and how they inspired him later on.

Right. Even his interest in the French eighteenth century becomes more understandable when you explore where that began, when he’s sitting there as a boy in [1930s] Germany, in one of the darkest moments in history—a completely devastated country, morally, physically. Suddenly, he finds out about this incredible, glittering world—the world of eighteenth-century France—and he becomes obsessed with it for the rest of his life. If you’re surrounded by all of this darkness, and you read about this moment of enlightenment, of course that’s going to be appealing.

It was also interesting for me to think about the writers from that era who were important to him. Princess Palatine, for example. Karl wanted to write a biography about her at one point. He was so obsessed with her. Or [Henri de] Saint-Simon. Karl loved his voice. There are so many elements of the eighteenth century that were important to him. But I realized that, for someone who is sensitive and creative in the middle of such destruction and such dark times, when you hear about something like this, of course you’re going to be interested in it.

I loved that quote of his, “To be more French than the French, you have to be a foreigner,” because only an outsider can develop a love for the culture that’s purely aesthetic, and not driven by patriotism or chauvinism. And this adolescent fascination is really where that started.

Yes, exactly.

You write about how you and Karl developed a friendship during your time as Paris bureau chief of Women’s Wear Daily and W magazine. Can you describe that relationship? What compelled you to write his biography?

I first met Karl in January 1995. At that point, W and Women’s Wear Daily were two of the most important publications in the world of fashion. So something I tried to be fair about in the book is that we had a relationship that began as something that was mutually beneficial, in that I was a journalist, and it was my job to cover Paris. Karl was a major player in the city, so it was in my interest to cultivate him. Meanwhile, I represented two magazines that were important for him, so it was important for him to cultivate me. I just think it’s important to be clear on that. But then, also, you can tell when you have a relationship that begins in that way, that becomes more of a friendship, and that’s what happened. We worked a lot together over the years, and I was able to see that we did have a friendship. Karl was a worker, and I think he enjoyed people who were workers—he surrounded himself with people who really worked hard. I think he appreciated that in me.

I also try to be honest about the fact that I was not one of Karl’s best friends, but we were friendly. Then, to complicate things a little, I left Paris in 2000, and I moved back to New York. Then I moved down to Texas, to work on my first book [Double Vision: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil]. So I was away from here for nineteen years. During that time, I would see Karl from time to time, and I would do a story, and I would interview him. He even came to Texas one time when Chanel did a show in Dallas. I saw him there. Then, interestingly, the last time I saw Karl was December of 2016 in Paris, at this public event or fundraiser that is done every year during that time. He knew that I was working on this book in Texas, and I said to him, “I just want you to know that that book is going to be done. And it’s going to be good. And after it comes out, I want to talk with you about the idea of maybe doing something together.” And he said, “Huh, huh…” You know, he didn’t say no, but he certainly didn’t say yes. Also, I didn’t know it at that point, but he had already been suffering from cancer for about a year. So the last thing he wanted to do was to let someone in when he’s trying to shield everyone around him from that knowledge.

When Karl died in February 2018, I knew that he did not want to have a book about himself when he was alive. But when someone dies, maybe it sounds kind of callous to say this, but they become a historical figure. And I think he was too important of a person to not explore his life. It took a while to build relationships with people who were close to him, I think because a lot of people were protective of him and of his legacy, and knew that he didn’t want to focus too much on that when he was alive. For example, with my relationship with Chanel, it took a while to make them feel comfortable with the project and for them to see that it was a serious book. But they have been very helpful in providing unprecedented access to archival documents, and members of the national archives have very graciously fact-checked every version of this manuscript. They’ve done a very thorough job, and they’ve been very positive about the results.

Of course, when writing a biography, you come to know a person quite intimately. Has writing the book altered your perception of Karl at all from when you knew him personally? Or was it more of a magnification of what you knew?

There are definitely things that I learned about Karl. I’ve seen him differently in some ways. For instance, what we were saying about his interest in the eighteenth century, I have a deeper understanding now of where that comes from. One of the things I learned, which sounds like such a small piece of information, is that I knew that Karl always lied about his age, that he always shaved five years off of his age. But it wasn’t until I asked Gerhard Steidl, who worked with him for three decades as a publisher, about that issue. And he told me, “I don’t know if it was just because I was young, or because I was just starting out with Karl, but I decided to ask him, ‘Why do you always shave five years off your age? Why do you say you were born in 1938 when you were really born in 1933?’ And Karl answered, ‘I was ashamed. I was ashamed that I was born in the year when Hitler started his project of killing the Jewish population of Germany. And I did not want to be connected to that year.’” No one had ever asked him that—or he certainly had never responded in that way—so that was revelatory for me.

I think we all shade our story a little. So it was fun to discover that certain things were not entirely accurate. For instance, Karl always said that he was self-educated, which in a general sense is true, in terms of his historical knowledge, in terms of his literary knowledge. But I found through this amazing resource—a 1954 notebook that his mother put together from the year that he won the [International] Woolmark Prize—that he went to this fashion illustration school, the Cours Norero. No one had ever heard of the Cours Norero. No one had ever associated Karl with it. He was not a student there for a long time—it was for less than a year. But it was important for his development, and he always maintained a relationship with Madame [Andrée] Norero [Petitjean]. He invited her to his shows, he went to her funeral. This was a really important moment in his life that he never talked about.

Yeah, I definitely picked up on those little pieces. There are a lot of really interesting details of how he was shaping his narrative.

Right. And there are some things that are not knowable in real life. For example, to be honest, one thing that I have a hard time bringing into focus is his mother. When Karl recounts these incredibly harsh things that his mother said, they sound exactly like things that Karl would have said. Then there’s that one quote from a friend of Karl saying that she was like an ice pick. Then others say that she was incredibly cultured and charming. Others say she just kind of drifted through in the background. I think all I can do is put on the page what I know, and people can decide for themselves.

Was there an aspect of Karl’s life that you were most concerned with doing justice, or, in other words, about getting just right? Was there a certain aspect of his character or worldview that you were intent on getting across to the reader?

One of the biggest challenges is that Karl was so effective at crafting his public persona. He has this incredible image, and [as a biographer], you can just focus on the image. But my editor gave me the most incredible piece of direction. It might sound really obvious, but at the beginning of this process, she said, “We want to feel like we’re in the same room with Karl.” No one had ever given me that exact direction before, and it was super helpful because we don’t want to just look at the image. The image of Karl is there, and you see it throughout, but you really want to get to the person behind that image. You really want to be there with him. And the way to do that is through his words, and it’s also through interviews with people who knew him really well, and were in the room with him. I think that was the overarching biggest challenge: to get behind the mask, and to really look at the person.

Another thing that was important is that, while I have worked at fashion magazines, I’m not a fashion writer. My first perception of Karl, when I knew him in the nineties, was that there were other designers that were more important in terms of fashion, but that Karl was more important in terms of the culture. So I began this project thinking that, but the more research I did, and the more I looked at interviews with him in the sixties, reviews in the sixties, seventies, and early eighties before he even joined Chanel in 1983, I saw how important he was considered, decades before he started at Chanel, which is when everyone thinks he really established his reputation. When Karl started at Chanel, some people reacted with, “What is this German designer doing at Chanel? It’s outrageous: a German designer, a French institution.” But by the time I finished reading all of these reviews and studying all of this [material] from people who are fashion critics, I realized, of course Karl is going to Chanel. It just seems obvious to me when you really study where he was, and where he’d been for a long time. So that was interesting for me, to try to get his significance as a fashion designer right.

And what he did at Chanel is remarkable. No one had ever done that before: reinvigorated a historical house that was essentially bankrupt, and turned it into such a thriving force. It’s been done since, but he was really the first one to do it. And that is already fascinating. And then, in 2004, with H&M, he fused this idea of high fashion with the power of the mass market, and turned himself into, intentionally or not, a kind of global superstar. Up to that point, Karl was what might be called “fashion famous,” but after that, he was known by everyone, every socioeconomic level, every age group, all over the world.

You interviewed a wide swath of characters from Karl’s world for the book. Which of your interviews shed the most light on Karl’s inner life? Was there anything you learned from these conversations that surprised you?

Two interview subjects that were essential are Michel Gaubert, who did the music for all of Karl’s shows from 1989 until he died in 2019, and Stefan Lubrina, who did all the sets for Chanel, and for every show that Karl did. Both of those interviews are fascinating, because, particularly once Karl was doing Chanel shows at the Grand Palais in Paris, they were these incredible shows that were covered all around the world, that made news on the BBC and news programs everywhere. But those didn’t just happen. It was a team that made them happen. So to really speak with Stefan Lubrina about the way that he worked with Karl to develop these ideas was fascinating. There’s a little moment that I love with one of the most spectacular shows they did. Karl said, “I want to do a show with a rocket,” and Stefan is thinking about it: “So there has to be a launching pad, and then what’s going to happen?” And then eventually, he says, “Karl, well, I think the rocket has to lift off,” and Karl says, “Well, of course it has to lift off.” But he didn’t say that at the beginning. It’s been said that that’s the way they would work. They had this kind of collaboration, this thought process, and they would spend nine, ten months on a twelve- or fifteen-minute show. The show with the rocket was news all around the world, and not just fashion news. It was, “Chanel now has a rocket taking off at a show at the Grand Palais.”

So many people who were close to Karl in a specific area of his life, or at a specific time, brought something interesting to the book. The Anna Wintour interview is important when it comes to Karl as a designer, but she also shows a very human side of Karl. She talks about how sad and how difficult the last show that he did in New York in December 2018 was, because it was clear that he was very sick. He died two months later. Or there’s Silvia Venturini Fendi, who knew Karl from the time she was five years old, I believe. She was the last person to talk with him on the telephone the night before he died, and they were still talking about the Fendi show that was happening in two or three days in Milan, and they were trying to find a way to get him there.

Some of the people who were around Karl on a daily basis were the people who were most interesting for me, like Sébastien Jondeau, his right-hand man, bodyguard, and chauffeur, who was with him when he died. To try to do justice to that relationship was important for me. The butler, Frédéric Gouby, was super interesting, too, because again, he was there every day, and he really gives you a sense of what Karl was like when he was off-stage. Even someone like Françoise Caçote, who oversees Choupette, Karl’s cat. I think she helped me to see the significance that Choupette had, and what she really meant to Karl. When I thought about it, I realized that he hadn’t had an emotional relationship like that since Jacques de Bascher died.

I loved all the details about Choupette, and that quote where Karl says, “I don’t have any boss other than myself and Choupette.” It really goes to show how important she was to him.

There’s that moment from Silvia Venturini Fendi, where she said she would get a little text from Karl with a picture of Choupette: “Choupette says good morning,” “Choupette says good night.” And she’s like, of course it wasn’t Choupette, it was Karl. But Karl could sometimes have a hard time expressing his emotions. And Choupette was a way for him to say you’re a part of my little family. To me, that’s lovely.

This year’s Costume Institute exhibition is dedicated to Karl. You mentioned earlier that Karl didn’t want a book released about him during his life, and he also adamantly refused to attend the opening of his own retrospective toward the end of his career. In reference to his own death, he even once said: “My own grave? Quelle horreur! Burnt—tossed—done! I hate the idea of burdening people with remains. Just get out of town—disappear. I admire these animals that just go off into virgin forest—when it’s over, it’s over.” I’m wondering, given these views, how do you think he would react to these grand tributes this year?

Had he been alive, he would’ve been horrified. But he also said that [Cristóbal] Balenciaga and [Coco] Chanel never had retrospectives while they were alive, but he wasn’t opposed to Balenciaga and Chanel retrospectives, because retrospectives clarify their significance as a designer. So I think that Karl now would probably approve. He worked hard, and he felt like designers who focus on their recent past while they’re alive are sort of admitting that it’s all over—that there’s something funereal about that. That’s what he didn’t want. That’s actually where the title of the book comes from: the fact that he’s completely focused on the present.

What do you think Karl will be most remembered for?

I think he will be remembered for what he did at Chanel, and for having turned himself into almost an avatar—for having become a public figure that creates as much interest as his work. As far as his work at Chanel—he was also incredibly successful at Chloé, incredibly successful at Fendi, and eventually, Karl Lagerfeld, his own brand, became incredibly successful as well, and still is—but I think that the idea of taking the spirit of an older, historic house and making it modern in a way that is historically accurate, and playful, and exciting, is an idea that really began with Karl.

Then there’s what he did with his own persona. I mention this [anecdote] in the acknowledgments where he’s being photographed by Jean-Baptiste Mondino, and he has to leave to go into the other room to have his hair and makeup touched up, and he says, “Time to go freshen up the marionette!” That’s someone who’s very conscious of the effect that they’re having, and that it’s an act, and that it’s a persona that they’ve created. I think those, for me, are the two biggest lessons from Karl: how to reinvigorate a historic house like Chanel, and [how he invented] his own character.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.