At the ICA Philadelphia, Sissel Tolaas Presents Smell as a Poetic Provocation

Walking into the cavernous first-floor gallery of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Philadelphia—where “RE_________,” an exhibition by the Norwegian-born, Berlin-based artist Sissel Tolaas is currently on view (through Dec. 30)—feels like stepping into a scientist’s laboratory, if the scientist it belonged to had also studied minimal sculpture. There’s a wall of small vials printed with the artist’s name, each containing a bit of clear liquid. Plastic tubes and metal piping run high along the gallery, carrying who knows what to who knows where. Others descend from the ceiling towards concrete reservoirs that have been raised from the floor. One of them is disgorging, drop by drop, a bit of unknown liquid. In the center of the room, an assembly of large flasks, some of which are bubbling, releasing visible vapor into the air, surrounds a huge pillar. Beyond it is a long, multilevel plinth covered in small objects; in the center of the floor, an assemblage of glass sculptures, seemingly empty.

The largest presentation of the artist’s work to date, the ICA show fills both floors of the museum with Tolaas’s carefully constructed artworks that use the act of smelling to consider large-scale social topics such as the climate crisis, evolution, anthropology, and geopolitics.

I look around, but none of the pieces have any written explanation. On the wall is a large diagram of lines and numbers, with a small key in the lower left-hand corner that marks certain nodes in the diagram with the following five categories: Identity, Memory, Power, Communication, and Environment. Deprived of text to orient myself, I’m left to smell my way around the room.

I drift towards the long plinth, covered in objects. Some of them are organic, almost like pumice stones. Others are 3D-printed plastic, their forms vaguely crystalline. I pick them up one by one and start to smell. Some of the scents are immediately familiar, pulsing with clarity: cinnamon, grape, lilac, lime. Some conjure images or situations: a hot tub, a barnyard, frankincense in a stone church. Certain objects spark hazy memories of scents I can’t quite place. Without any other signifying information, these smells remain amorphous but evocative. One of them in particular, which I return to several times, smells alternately like parmesan and like the body odor of a past lover.

It is this specific scent that, for me, activates the exhibition’s unexpected poetry. Standing in a room thick with odors, but with no instructional language to collapse my experience of them into any “correct” interpretation, I’m forced to consider the information of my senses, forced to spend time in a mindset where meaning is produced and confirmed according to an alternate framework. I’m forced to trust my own impressions, to be the ultimate arbiter of my own experience.

Later, I learn this is exactly what Tolaas intends. “Challenging people to use their noses gives them new methods to approach their realities,” she says. “Our society and culture have traditionally been dominated by the visual. Vision clearly distances us from the objects we see. By contrast, smells surround, penetrate the body, and permeate the immediate environment, and thus one’s response involves a very strong memory effect.”

As I wander through the exhibition, I’m presented with works that ask more of me than I’m used to. Rather than reading some wall text, glancing at a piece, and moving on, consuming the show in an easy chain, I’m invited to participate, to wonder, to think beyond what smells “good” or “bad.” This invitation grows out of Tolaas’s thinking about smell and culture. Discussing the way modernity has contrived to suppress smell as a useful and universal source of information, she describes the idea of something smelling good or bad as a binary that is used to reinforce separation between classes of people. “Smell codes continue to be allowed to reinforce social hierarchies,” she says, perpetuating “rhetoric that contributes to dividing rather than connecting us.”

When a smell gets defined as good or bad, it also becomes encoded with value judgments. These judgments, Tolaas argues, are not neutral or universal, but are instead bound up in culture and place: “What constitutes an acceptable smell environment? Who makes the rules?” By removing the visual and linguistic markers that carry these value judgments, Tolaas wants us to smell, and to think, for ourselves. Her hope is that this will reveal, as she puts it, “the interrelation of smell, power, and society.”

For curator Zoë Ryan, the ICA’s director who organized the presentation (it was previously shown at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo), Tolaas’s methodology of stripping away context around smell gives the work a complex power. “It’s quite bodily, it’s visceral, it’s physical, it’s sensorial,” she says. But, she says, it also tackles “so many issues, it’s so multilayered.” When I mention the initial disorientation I experienced when I realized there wasn’t any wall text, Ryan points me toward thinking about this as part of the artist’s aim. “Sissel is really interested in how we can trust ourselves more,” she says, “and that disorientation is a reminder that we aren’t used to that.”

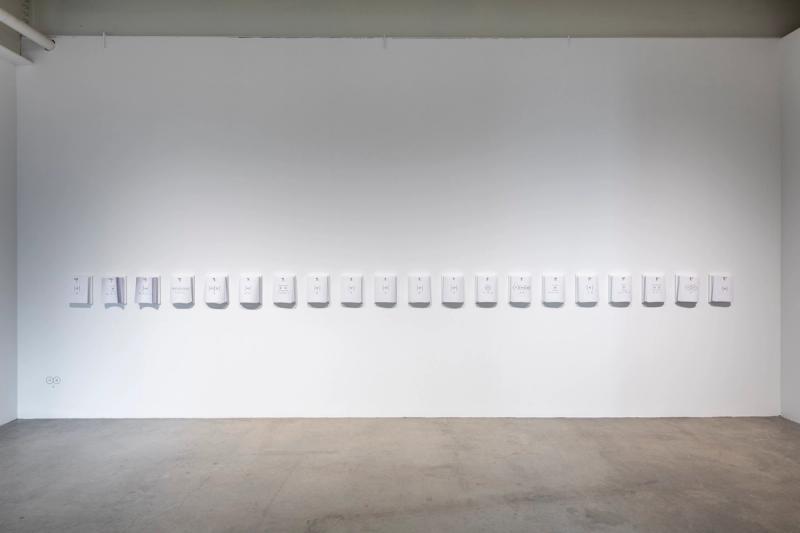

As I turn the corner to the exhibition’s final room, I see a neat row of stacks of printouts hanging on the wall. These are marked with numbers and symbols, the same ones that made up the large diagram on the wall of the first-floor gallery. Taking one, I turn it over and see that it has all of the information I was looking for when I entered the show: the name of a work, its dates, and explanatory text that reveals the content and intention behind it. I take one of each, assembling a stack of reading material, but holding them in my hands, I realize I don’t want to read them right away. I want to linger in the pleasant state of not-quite-knowing produced by this singular artist for this singular exhibition, to spend a little more time wondering.